- All the reasons

- By theme

- Jesus

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- The martyrs

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

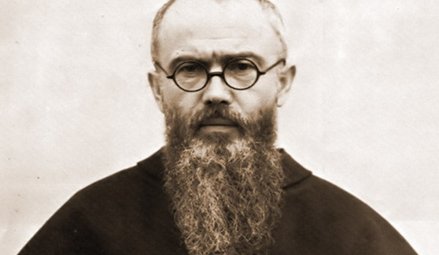

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Visionaries

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- Stigmates

- Eucharistic miracles

- Relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- Who are we?

- Make a donation

EVERY REASON TO BELIEVE

Les martyrs

n°67

Paris, France

1794

The sixteen Carmelite martyrs of Compiègne - 1794

The 18th century French revolutionaries regarded cloistered and contemplative religious life as an attack on individual freedom and an outdated religious practice, and made it illegal. Yet the contemplative Carmelite nuns in Compiègne, northest of Paris, managed to remain faithful to their vows until the end. At the height of the Reign of Terror, they were accused of being counter-revolutionaries and religious fanatics, imprisoned and sentenced to death. All sixteen of them were guillotined on July 17, 1794 (29 Messidor of Year II). They had first made an offering of their lives as sacrificial victims to obtain peace for the Church and for their country, and ascended the scaffold singing hymns of praise to God.

Execution of the Carmelites, stained glass window in the church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Quidenham, England / © CC BY-SA 2.0/John Salmon

Reasons to believe:

- One of the nuns who was away during the arrests and survived, Sister Mary of the Incarnation, later wrote an account on their execution, The Story of the Martyrdom of the Sixteen Carmelites of Compiègne, which was published in 1836, forty years after the events. The account of their martyrdom was also told by their fellow inmates, the English Benedictine nuns of Cambrai, who survived.

- The Carmelites of Compiègne were not foolish and did not wish to die: they agreed to take some oaths demanded by the revolutionaries, provided that they could maintain their religious vows.

- We have proof of their courage, free will and strength of convictions: when forced to leave the convent and hide in different apartments in the city, they courageously continued to practice community prayer, despite the government's orders. They all refused to renounce their religious vows, and they later recanted their civil oath while in prison.

- Paradoxically, it was at the Conciergerie Prison that the Carmelites had the joy of once again being able to experience community life. A witness called Denis Blot testified: "We could hear them every night, at two in the morning, reciting their office." Their serene joy made a strong impression on both prisoners and jailers: "They looked like they were going to their wedding."

- At the end of the 17th century, one century before the French Revolution, a Carmelite nun from this same monastery, Sister Elisabeth-Baptiste, had a dream in which she saw all her Carmelite sisters in the glory of heaven, dressed in their white cloaks and holding a red palm in their hands. Their martyrdom had been foretold several decades in advance, and the nuns were preparing for it.

- Unlike regular executions, when the nuns arrived at the place of execution, the crowd went very quiet. The nuns sang and climbed the scaffold one after the other, with a joyful resolve. Their attitude disconcerted the stunned crowd, as well as the hardened executioner Charles-Henri Samson. Witnesses said that the novice nun, who was the first to climb the scaffold, "looked like a queen about to receive a diadem".

- For the Carmelite nuns, martyrdom was not a tragedy but a celebration, because they were sure that their ultimate destination was eternal life with God. This is why they were able to sing on the scaffold up to the last minute.

- The Carmelites believed: "We are the victims of the age, and we ought to sacrifice ourselves to obtain its return to God." According to the act of consecration pronounced by these nuns in 1792, the purpose of their voluntary sacrifice was that the "divine peace that [Christ] had come to bring to the world should be restored to the Church and the State". In fact, the spectacle of their unjust death and courage changed public opinion, making it aware of the horror of revolutionary violence. Eleven days after their execution by beheading, the fall of Robespierre put an end to the Reign ofTerror.

- Several miracles were obtained through the intercession of the Carmelites. At least four of these miracles were investigated, attested and used for the beatification of the sixteen nuns: the cure of Sister Clare of St. Joseph, a Carmelite lay sister of New Orleans, when on the point of death from cancer, in June, 1897; the cure of the Abbe Roussarie, of the seminary at Brive, when at the point of death, March 7, 1897; the cure of Sister St. Martha of St. Joseph, a Carmelite lay sister of Vans, of tuberculosis and an abcess in the right leg, December 1, 1897; the cure of Sister St. Michael, a Franciscan of Montmorillon, April 9, 1898.

Summary:

The sixteen Carmelite nuns were slowly transported through the streets of Paris, for two hours, on a tumbrel (two-wheeled cart) that took them to their execution at the Place du Trône Renversé (now Place de la Nation) on July 17, 1794 (29 Messidor Year II). The Reign of Terror had descended on France, but until then this religious community had been spared by keeping a low profile. On that day, the civilian clothes they had been forced to wear were being washed, so it was in their habit (with a large white coat) that they climbed up the scaffold. They sang the psalm "Laudate Dominum", traditionally sung at the founding of a Carmelite convent, as they set off to establish their community in eternity.

This sacrifice of innocent women drew a large crowd. Eleven days later, the Reign of Terror came to an end with the fall of Robespierre on 9 Thermidor (he was guillotined, despite an attempt by a deputation from the Paris Commune to save him). Russian author AleksandrSolzhenitsyn saw the self-sacrifice of the nuns as the cause of the return to peace in France, and compared the militant-atheist Russian Revolution and USSR, which persecuted religion and committed mass atrocities over decades, to the godless French Revolution.

The lives and arrests of these French Carmelite nuns have inspired a number of major works: a novel (by Gertrude von Le Fort), a script (by Georges Bernanos), an opera (by Francis Poulenc), films (including one by Philippe Agostini and Father Bruckberger OP), etc. Father Bruckberger was deeply touched by the nun's fidelity, an example he only imitated later in life, he said.

At the request of the bishops of France and the Order of Carmelites Discalced (OCD), Pope Francis agreed on Feb. 22, 2022, to open a special process known as “equipollent canonization” to raise the 16 Carmelite martyrs of Compiègne to the altars. After their beatification by Pius X in 1906, canonization will elevate them from blessed to saints. In deference to the French government, they are not labeled as martyrs. Yet it was out of hatred for the Catholic faith that they were beheaded.

Eric Lebec is an author, television director, journalist and writer. A long conversation with Father Bruckberger (o.p.) introduced him to the Carmelites of Compiègne.

Going further:

To Quell the Terror: The True Story of the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiegne by William Bush – JICS Publications; Limited edition (January 1, 1999)