- By theme

- Jesus

- The many proofs of Christ’s resurrection

- Saint Thomas Aquinas: God gave all the divine proofs we needed to believe

- The surpassing power of Christ's word

- Lewis’s trilemma: a proof of Jesus’s divinity

- God saves: the power of the holy name of Jesus

- Jesus spoke and acted as God's equal

- Jesus' divinity is actually implied in the Koran

- Jesus came at the perfect time of history

- Rabbinical sources testify to Jesus' miracles

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- An enduring prophecy and a series of miraculous events preventing the reconstruction of the Temple

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- Saint Peter, prince of the apostles

- Saint John the Apostle: an Evangelist and Theologian who deserves to be better known (d. 100)

- Saint Matthew, apostle, evangelist and martyr (d. 61)

- James the Just, “brother” of the Lord, apostle and martyr (d. 62 AD)

- Saint Matthias replaces Judas as an apostle (d. 63)

- The martyrs

- The protomartyr Saint Stephen (d. 31)

- Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, disciple of John and martyr (d. 155)

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Agatha stops a volcano from destroying the city of Catania (d. 251)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The martyrdom of Paul Miki and his companions (d. 1597)

- The martyrs of Angers and Avrillé (1794)

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- He braved torture to atone for his apostasy (d. 1818)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

- José Luis Sanchez del Rio, martyred at age 14 for Christ the King (d. 1928)

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- The Desert Fathers (3rd century)

- Saint Anthony of the Desert, a father of monasticism (d. 356)

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The surprising death of Father Emmanuel de Floris (d. 1992)

- The prophecies of Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (d. 1994)

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Rose of Viterbo or How prayer can transform the world (d. 1252)

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence (d. 1317)

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

- Saint Peter Thomas (d. 1366): a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love (d. 1510)

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Saint Marie of the Incarnation, "the Teresa of New France" (d.1672)

- St. Francis di Girolamo's gift of reading hearts and souls (d. 1716)

- Rosa Venerini: moving in the ocean of the Will of God (d. 1728)

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833): the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

- Camille de Soyécourt, filled with divine fortitude (d. 1849)

- Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary (1858)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin" (d. 1862)

- Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble (1863)

- Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church (d. 1872)

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God” (d. 1919)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Lutgardis of Tongeren and the devotion to the Sacred Heart

- Saint Angela of Foligno (d. 1309) and "Lady Poverty"

- Saint John of the Cross: mystic, reformer, poet, and universal psychologist (+1591)

- Blessed Anne of Jesus: a Carmelite nun with mystical gifts (d.1621)

- Catherine Daniélou: a mystical bride of Christ in Brittany

- Saint Margaret Mary sees the "Heart that so loved mankind"

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée of Jesus' predictions concerning the Second World War (1922)

- Sister Josefa Menendez, apostle of divine mercy (d. 1923)

- Edith Royer (d. 1924) and the Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre

- Rozalia Celak, a mystic with a very special mission (d. 1944)

- Visionaries

- Saint Perpetua delivers her brother from Purgatory (203)

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Discovery of the Virgin Mary's house in Ephesus (1891)

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- Maria Valtorta's visions match data from the Israel Meteorological Service (1943)

- Berthe Petit's prophecies about the two world wars (d. 1943)

- Maria Valtorta saw only one pyramid at Giza in her visions... and she was right! (1944)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Saint Augustine's conversion: "Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?" (386)

- Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534): a life in service of the truth

- Madame Acarie, "the servant of the servants of God" (d. 1618)

- Blaise Pascal (d.1662): Biblical prophecies are evidence

- Madame Élisabeth and the sweet smell of virtue (d. 1794)

- Jacinta, 10, offers her suffering to save souls from hell (d. 1920)

- Father Jean-Édouard Lamy: "another Curé of Ars" (d. 1931)

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- The Christian faith explains the diversity of religions

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Our Lady of Virtues saves the city of Rennes in Bretagne (1357)

- Mary stops the plague epidemic at Mount Berico (1426)

- Our Lady of Miracles heals a paralytic in Saronno (1460)

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- Savona: supernatural origin of the devotion to Our Lady of Mercy (1536)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- The “aldermen's vow”, or the Marian devotion of the people of Lyon (1643)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- Heaven confides in a shepherdess of Le Laus (1664-1718)

- Zeitoun, a two-year miracle (1968-1970)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- The five Marian apparitions that traced an "M" over France, and its new pilgrimage route

- A series of Marian apparitions and prophetic messages in Ukraine since the 19th century (1806)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- "Our Lady of the Poor" appears eight times in Banneux (1933)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Mary responds to the Vows of the Polish Nation (1956)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Seuca, Romania: apparitions and pleas of the Virgin Mary, "Queen of Light" (1995)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Mont Saint-Michel: Heaven watching over France

- Angels give a supernatural belt to the chaste Thomas Aquinas (1243)

- The constant presence of demons and angels in the life of St Frances of Rome (d. 1440)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée escapes from prison with the help of an angel (1943)

- Saved by Angels: The Miracle on Highway 6 (2008)

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Peter Nolasco: a life dedicated to ransoming enslaved Christians (d. 1245)

- Saint Angela Merici: Christ came to serve, not to be served (d. 1540)

- Saint John of God: a life dedicated to the care of the poor, sick and those with mental disorders (d. 1550)

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Blessed Alix Le Clerc, encouraged by the Virgin Mary to found schools (d. 1622)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montreal's first teacher (d. 1700)

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Damian of Molokai: a leper for Christ (d. 1889)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Saint Dulce of the Poor, the Good Angel of Bahia (d. 1992)

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- The miracle of liquefaction of the blood of St. Januarius (d. 431)

- The miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua (d. 1231)

- Saint Pius V and the miracle of the Crucifix (1565)

- Saint Philip Neri calls a teenager back to life (1583)

- The resurrection of Jérôme Genin (1623)

- Saint Francis de Sales brings back to life a victim of drowning (1623)

- Saint John Bosco and the promise kept beyond the grave (1839)

- The day the sun danced at Fatima (1917)

- Pius XII and the miracle of the sun at the Vatican (1950)

- When Blessed Charles de Foucauld saved a young carpenter named Charle (2016)

- Reinhard Bonnke: 89 million conversions (d. 2019)

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Our Lady at Pellevoisin: "I am all merciful" (1876)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- Gemma Galgani: healed to atone for sinners' faults (d. 1903)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The extraordinary healing of Alice Benlian in the Church of the Holy Cross in Damascus (1983)

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Healed by St Charbel Makhlouf, her scars bleed each month for the benefit of unbelievers (1993)

- The miracle that led to Brother André's canonisation (1999)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- He had “zero” chance of living: a baby's miraculous recovery (2015)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Dying in the odour of sanctity

- The body of Saint Cecilia found incorrupt (d. 230)

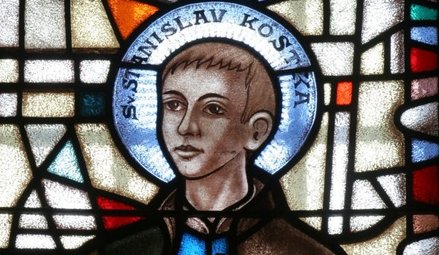

- Stanislaus Kostka's burning love for God (d. 1568)

- Blessed Antonio Franco, bishop and defender of the poor (d. 1626)

- The incorrupt body of Marie-Louise Nerbollier, the visionary from Diémoz (d. 1910)

- The great exhumation of Saint Charbel (1950)

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Saidnaya icon exudes a wonderful fragrance (1988)

- Our Lady weeps in a bishop's hands (1995)

- Stigmates

- The venerable Lukarda of Oberweimar shares her spiritual riches with her convent (d. 1309)

- Blessed Maria Grazia Tarallo, mystic and stigmatist (d. 1912)

- Saint Padre Pio: crucified by Love (1918)

- Elena Aiello: "a Eucharistic soul"

- A Holy Triduum with a Syrian mystic, witnessing the sufferings of Christ (1987)

- A Holy Thursday in Soufanieh (2004)

- Eucharistic miracles

- Lanciano: the first and possibly the greatest Eucharistic miracle (750)

- A host came to her: 11-year-old Imelda received Communion and died in ecstasy (1333)

- Faverney's hosts miraculously saved from fire

- A tsunami recedes before the Blessed Sacrament (1906)

- Buenos Aires miraculous host sent to forensic lab, found to be heart muscle (1996)

- Relics

- The Veil of Veronica, known as the Manoppello Image

- For centuries, the Shroud of Turin was the only negative image in the world

- The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

- Saint Louis (d. 1270) and the relics of the Passion

- The miraculous rescue of the Shroud of Turin (1997)

- A comparative study of the blood present in Christ's relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Francis Xavier Samson Libermann, Jewish convert to Catholicism (1824)

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal and the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne (1842)

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- The conversion of an executioner during the Terror (1830)

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- Dazzled by God: Madeleine Delbrêl's story (1924)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Nelly Gillant: from Reiki Master to Disciple of Christ (2018)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Jesus audibly calls Alphonsus Liguori to follow him (1723)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Alicja Lenczewska: conversations with Jesus (1985)

- Vassula Ryden and the "True Life in God" (1985)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Invited to the celestial court: the story of Chantal (2017)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- Seven golden stars reveal the future location of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery (1132)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Saint Zita and the miracle of the cloak (13th c.)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- A celestial music comforts Elisabetta Picenardi on her deathbed (d. 1468)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- The strange adventure of Yves Nicolazic (1623)

- Julien Maunoir miraculously learns Breton (1626)

- Pierre de Keriolet: with Mary, one cannot be lost (1636)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- A hundred years before it happened, Saint Andrew Bobola predicted that Poland would be back on the map (1819)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Don Bosco's angel dog: Grigio (1854)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- Lost for over a century, a Russian icon reappears (1930)

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- He should have died of hypothermia in Soviet jails (1972)

- God protects a secret agent (1975)

- Flowing lava stops at church doors (1977)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- The miracles of Saint Juliana of Nicomedia (1994)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- The providential finding of the Mary of Nazareth International Center's future site (2000)

- Syrian Monastery shielded from danger multiple times (2011-2020)

- Jesus

- Who are we?

- Make a donation

TOUTES LES RAISONS DE CROIRE

Corps conservés des saints

n°128

1st century - present day

Dying in the odour of sanctity

The expression "to die in the odour of sanctity" is not a figure of speech. There are many documented examples of this occurrence throughout the course of history, beginning in the 1st century of our era. It is still happening today, even among ordinary people who have lived holy lives. The perceived fragrance is a mix of rose and violet scents, which have an obvious symbolic meaning, indicating that the person lived a life of great love and humility.

Variety of rose / © CC BY-SA 3.0

Les raisons d'y croire :

- The historian Waldemar Deonna, professor at the University of Geneva, lists at least 30 saints who gave off a mysterious scent when they were alive, 103 who did so when they died, and 347 saints whose bodies remained pleasantly fragrant long after they were buried. In view of the number of people who testify to this characteristic odour of sanctity, it is highly unlikely that each case is a lie or a collective olfactory hallucination.

- Take, for example, the case of Saint Margaret of Hungary (d. 1270): the many people who came to pay their respects after she passed attest to a very particular smell emanating from her body, a flowery smell that is highly unlikely to exist in January. Then there is Saint Teresa of Avila (d. 1582), whose body was hastily buried in a pit; it was the scent emanating from her burial place that permitted her body (still incorrupt) to be found. We could also mention Saint Rita of Cascia, Saint Padre Pio, Saint Narcissus of Jesus, and many others.

- The further back we go in Christian history, the less we can verify the facts and sort out the truth from pious exaggerations, and a smell tend to be difficult to prove. However, the continuation of the phenomenon in modern times allows us to form a better idea of what the odour of sanctity consists of and to find first-hand witnesses.

Synthèse :

Saint Margaret of Hungary (1242 - 1271) was nicknamed by her contemporaries "the fragrant rose in God's garden". From the age of 12, her piety was deep. She refused a marriage proposal, preferring to become a nun. Her life was filled with mystical graces and self-mortification. She had to fight against her family's desire to marry her off for political reasons, preferring to live a life of intense prayer. She died at the age of 29, exhausted by her penances. Her contemporaries testified that all around her exposed body, a strange perfume could be smelt, sweet and strong at the same time. The Church eventually canonised her, not because of this phenomenon, but because of the investigation into her life. She had developed three hearts, in the image of what the Fathers of the Church teach to define holiness: a heart of fire for God, a heart of stone for herself, and a heart of flesh for her neighbour. Her humility and charity were manifest.

Closer to our time is Narcisa de Jesús Martillo Morán (1832 - 1869), an Ecuadorian virgin and Dominican tertiary, known as "the little lily of Ecuador". Narcisa was a humble girl, who chose to an austere life of prayer and penance. No one would have paid any attention to her existence if, a century after her death, God had not manifested her soul through a number of miracles and exceptional phenomena, including the extraordinary fragrance of flowers. She is known in the region as the "Niña Narcisa". Not only was her body found intact 86 years after her death, but she was still exuding the same fragrance.

The Catholic Church, in her authority, gives this kind of phenomenon its rightful place: she verifies it and takes an interest in it. She records the accounts, but she is not satisfied with them. The investigation for canonisation focuses on the testimony of a life lived in holiness, which must be confirmed by one or more post-mortem established and significant miracles, not just prodigies, in which God shows that he wishes to make the person a model and intercessor.

Arnaud Dumouch is a Franco-belgian theologian and author specialised in eschatology. In 2013, Dumouch and Father Henri Ganty founded the Institut Docteur Angélique, which offers a complete online training programme in Catholic philosophy and theology, using Benedict XVI's hermeneutics of continuity.

Au-delà des raisons d'y croire :

What is the difference between a miracle and a prodigy?

Miracles (divine cause) go beyond the fundamental laws of nature and can never be explained by anything other than the infinite power of the Creator: for example, the resurrection of a decomposed corpse.

A prodigy (a possible natural cause) can have a possible explanation: for example, the resuscitation of a person who has been in cardiac arrest for a few minutes. Dying in the odour of sanctity is certainly a prodigy, although the cause is - in attested cases - the intervention of angels.

Aller plus loin :

MIRACLES OF THE SAINTS! Signs and Wonders from God: Miraculous Bodily Phenomena! by Michael Freze, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (March 2, 2016)

En savoir plus :- A Short Account of the Life and Virtues of the Venerable and Religious Mother, Mary of the Holy Cross: Abbess of the English Poor Clares at Rouen : ... Sweet Odour of Sanctity, March 21, Anno 1735 by Minister A. B, Wentworth Press (August 27, 2016)

The Holy Man Of Tours: Or, The Life Of Léon Papin-dupont, Who Died At Tours In The Odor Of Sanctity, March 18, 1876 by Pierre Désiré Janvier, Legare Street Press (October 26, 2022)

Life of Sister Mary of Jesus Crucified Who Died in the Odour of Sanctity in the Carmel of Bethlehem 1846-1878 by Peter F. Sfeir, Carmelite Convent (January 1, 1927)

Video What is "ODOR OF SANCTITY" ? Saints who emanate fragrant smells

The Holy Man Of Tours: Or, The Life Of Léon Papin-dupont, Who Died At Tours In The Odor Of Sanctity, March 18, 1876 by Pierre Désiré Janvier, Legare Street Press (October 26, 2022)

Life of Sister Mary of Jesus Crucified Who Died in the Odour of Sanctity in the Carmel of Bethlehem 1846-1878 by Peter F. Sfeir, Carmelite Convent (January 1, 1927)

Video What is "ODOR OF SANCTITY" ? Saints who emanate fragrant smells