- By theme

- Jesus

- The many proofs of Christ’s resurrection

- Saint Thomas Aquinas: God gave all the divine proofs we needed to believe

- The surpassing power of Christ's word

- Lewis’s trilemma: a proof of Jesus’s divinity

- God saves: the power of the holy name of Jesus

- Jesus spoke and acted as God's equal

- Jesus' divinity is actually implied in the Koran

- Jesus came at the perfect time of history

- Rabbinical sources testify to Jesus' miracles

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- An enduring prophecy and a series of miraculous events preventing the reconstruction of the Temple

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- Saint Peter, prince of the apostles

- Saint John the Apostle: an Evangelist and Theologian who deserves to be better known (d. 100)

- Saint Matthew, apostle, evangelist and martyr (d. 61)

- James the Just, “brother” of the Lord, apostle and martyr (d. 62 AD)

- Saint Matthias replaces Judas as an apostle (d. 63)

- The martyrs

- The protomartyr Saint Stephen (d. 31)

- Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, disciple of John and martyr (d. 155)

- Justin Martyr: philosopher and apologist (d.165)

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Agatha stops a volcano from destroying the city of Catania (d. 251)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Saint Boniface propagates Christianity in Germany (d. 754)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The martyrdom of Paul Miki and his companions (d. 1597)

- The martyrs of Angers and Avrillé (1794)

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- He braved torture to atone for his apostasy (d. 1818)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

- The Uganda martyrs: a recurring pattern in the persecution of Christians (1885)

- José Luis Sanchez del Rio, martyred at age 14 for Christ the King (d. 1928)

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- The Desert Fathers (3rd century)

- Saint Anthony of the Desert, a father of monasticism (d. 356)

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The surprising death of Father Emmanuel de Floris (d. 1992)

- The prophecies of Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (d. 1994)

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Augustine of Canterbury evangelises England (d. 604)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

- Saint Rainerius of Pisa: from musician to merchant to saint (d. 1160)

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Rose of Viterbo or How prayer can transform the world (d. 1252)

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence (d. 1317)

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

- Saint Peter Thomas (d. 1366): a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love (d. 1510)

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Saint Marie of the Incarnation, "the Teresa of New France" (d.1672)

- St. Francis di Girolamo's gift of reading hearts and souls (d. 1716)

- Rosa Venerini: moving in the ocean of the Will of God (d. 1728)

- Saint Jeanne-Antide Thouret: heroic perseverance and courage (d. 1826)

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833): the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

- Camille de Soyécourt, filled with divine fortitude (d. 1849)

- Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary (1858)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin" (d. 1862)

- Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble (1863)

- Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church (d. 1872)

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God” (d. 1919)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Lutgardis of Tongeren and the devotion to the Sacred Heart

- Saint Angela of Foligno (d. 1309) and "Lady Poverty"

- Saint John of the Cross: mystic, reformer, poet, and universal psychologist (+1591)

- Blessed Anne of Jesus: a Carmelite nun with mystical gifts (d.1621)

- Catherine Daniélou: a mystical bride of Christ in Brittany

- Saint Margaret Mary sees the "Heart that so loved mankind"

- Jesus makes Maria Droste zu Vischering the messenger of his Divine Heart (d. 1899)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée of Jesus' predictions concerning the Second World War (1922)

- Sister Josefa Menendez, apostle of divine mercy (d. 1923)

- Edith Royer (d. 1924) and the Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre

- Rozalia Celak, a mystic with a very special mission (d. 1944)

- Visionaries

- Saint Perpetua delivers her brother from Purgatory (203)

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Discovery of the Virgin Mary's house in Ephesus (1891)

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- Maria Valtorta's visions match data from the Israel Meteorological Service (1943)

- Berthe Petit's prophecies about the two world wars (d. 1943)

- Maria Valtorta saw only one pyramid at Giza in her visions... and she was right! (1944)

- The location of Saint Peter's village seen in a vision before its archaeological discovery (1945)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- Mariette Kerbage, the seer of Aleppo (1982)

- The 20,000 icons of Mariette Kerbage (2002)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Saint Augustine's conversion: "Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?" (386)

- Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534): a life in service of the truth

- Madame Acarie, "the servant of the servants of God" (d. 1618)

- Blaise Pascal (d.1662): Biblical prophecies are evidence

- Madame Élisabeth and the sweet smell of virtue (d. 1794)

- Jacinta, 10, offers her suffering to save souls from hell (d. 1920)

- Father Jean-Édouard Lamy: "another Curé of Ars" (d. 1931)

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- The Christian faith explains the diversity of religions

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Apparition of Our Lady of La Treille in northern France: prophecy and healings (600)

- Our Lady of Virtues saves the city of Rennes in Bretagne (1357)

- Mary stops the plague epidemic at Mount Berico (1426)

- Our Lady of Miracles heals a paralytic in Saronno (1460)

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- Savona: supernatural origin of the devotion to Our Lady of Mercy (1536)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- The “aldermen's vow”, or the Marian devotion of the people of Lyon (1643)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- Heaven confides in a shepherdess of Le Laus (1664-1718)

- Zeitoun, a two-year miracle (1968-1970)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- The five Marian apparitions that traced an "M" over France, and its new pilgrimage route

- A series of Marian apparitions and prophetic messages in Ukraine since the 19th century (1806)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- "Our Lady of the Poor" appears eight times in Banneux (1933)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Mary responds to the Vows of the Polish Nation (1956)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Seuca, Romania: apparitions and pleas of the Virgin Mary, "Queen of Light" (1995)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Mont Saint-Michel: Heaven watching over France

- The revelation of the hymn Axion Estin by the Archangel Gabriel (982)

- Angels give a supernatural belt to the chaste Thomas Aquinas (1243)

- The constant presence of demons and angels in the life of St Frances of Rome (d. 1440)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée escapes from prison with the help of an angel (1943)

- Saved by Angels: The Miracle on Highway 6 (2008)

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Peter Nolasco: a life dedicated to ransoming enslaved Christians (d. 1245)

- Rita of Cascia forgives her husband's murderer (1404)

- Saint Angela Merici: Christ came to serve, not to be served (d. 1540)

- Saint John of God: a life dedicated to the care of the poor, sick and those with mental disorders (d. 1550)

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Blessed Alix Le Clerc, encouraged by the Virgin Mary to found schools (d. 1622)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montreal's first teacher (d. 1700)

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Damian of Molokai: a leper for Christ (d. 1889)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Saint Dulce of the Poor, the Good Angel of Bahia (d. 1992)

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- The miracle of liquefaction of the blood of St. Januarius (d. 431)

- The miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua (d. 1231)

- Saint Pius V and the miracle of the Crucifix (1565)

- Saint Philip Neri calls a teenager back to life (1583)

- The resurrection of Jérôme Genin (1623)

- Saint Francis de Sales brings back to life a victim of drowning (1623)

- Saint John Bosco and the promise kept beyond the grave (1839)

- The day the sun danced at Fatima (1917)

- Pius XII and the miracle of the sun at the Vatican (1950)

- When Blessed Charles de Foucauld saved a young carpenter named Charle (2016)

- Reinhard Bonnke: 89 million conversions (d. 2019)

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Our Lady at Pellevoisin: "I am all merciful" (1876)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- The miraculous healing of Marie Bailly and the conversion of Dr. Alexis Carrel (1902)

- Gemma Galgani: healed to atone for sinners' faults (d. 1903)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The extraordinary healing of Alice Benlian in the Church of the Holy Cross in Damascus (1983)

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Healed by St Charbel Makhlouf, her scars bleed each month for the benefit of unbelievers (1993)

- The miracle that led to Brother André's canonisation (1999)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- He had “zero” chance of living: a baby's miraculous recovery (2015)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Dying in the odour of sanctity

- The body of Saint Cecilia found incorrupt (d. 230)

- Saint Claudius of Besançon: a quiet leader, a calm presence, and a strong belief in the value of prayer (d. 699)

- Stanislaus Kostka's burning love for God (d. 1568)

- Saint Germaine of Pibrac: God's little Cinderella (d. 1601)

- Blessed Antonio Franco, bishop and defender of the poor (d. 1626)

- Giuseppina Faro, servant of God and of the poor (d. 1871)

- The incorrupt body of Marie-Louise Nerbollier, the visionary from Diémoz (d. 1910)

- The great exhumation of Saint Charbel (1950)

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Saidnaya icon exudes a wonderful fragrance (1988)

- Our Lady weeps in a bishop's hands (1995)

- Stigmates

- The venerable Lukarda of Oberweimar shares her spiritual riches with her convent (d. 1309)

- Florida Cevoli: a heart engraved with the cross (d. 1767)

- Blessed Maria Grazia Tarallo, mystic and stigmatist (d. 1912)

- Saint Padre Pio: crucified by Love (1918)

- Elena Aiello: "a Eucharistic soul"

- A Holy Triduum with a Syrian mystic, witnessing the sufferings of Christ (1987)

- A Holy Thursday in Soufanieh (2004)

- Eucharistic miracles

- Lanciano: the first and possibly the greatest Eucharistic miracle (750)

- A host came to her: 11-year-old Imelda received Communion and died in ecstasy (1333)

- Faverney's hosts miraculously saved from fire

- A tsunami recedes before the Blessed Sacrament (1906)

- Buenos Aires miraculous host sent to forensic lab, found to be heart muscle (1996)

- Relics

- The Veil of Veronica, known as the Manoppello Image

- For centuries, the Shroud of Turin was the only negative image in the world

- The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

- Saint Louis (d. 1270) and the relics of the Passion

- The miraculous rescue of the Shroud of Turin (1997)

- A comparative study of the blood present in Christ's relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Francis Xavier Samson Libermann, Jewish convert to Catholicism (1824)

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal and the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne (1842)

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Olivier's conversion story: from Pesach to the Christian Easter (2000)

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- He met Jesus while looking for Muhammad (1990)

- Selma's journey to baptism (1996)

- Soumia, converted to Jesus as she hears Christmas carols (2003)

- How Aïsha, a Muslim convert, found Jesus (2004)

- Amir chooses Christ, at the risk of becoming homeless (2004)

- Souad Brahimi: brought to Jesus by Mary (2012)

- Pursued by God: Khadija's story (2023)

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- The conversion of an executioner during the Terror (1830)

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- From agnostic to Catholic Trappist monk (1909)

- Dazzled by God: Madeleine Delbrêl's story (1924)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Nelly Gillant: from Reiki Master to Disciple of Christ (2018)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Jesus audibly calls Alphonsus Liguori to follow him (1723)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Jesus' message to Myrna Nazzour (1984)

- Alicja Lenczewska: conversations with Jesus (1985)

- Vassula Ryden and the "True Life in God" (1985)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Invited to the celestial court: the story of Chantal (2017)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Ambrose of Milan finds the bodies of the martyrs Gervasius and Protasius (386)

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- Seven golden stars reveal the future location of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery (1132)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Saint Zita and the miracle of the cloak (13th c.)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- A celestial music comforts Elisabetta Picenardi on her deathbed (d. 1468)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- The strange adventure of Yves Nicolazic (1623)

- Julien Maunoir miraculously learns Breton (1626)

- Pierre de Keriolet: with Mary, one cannot be lost (1636)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- A hundred years before it happened, Saint Andrew Bobola predicted that Poland would be back on the map (1819)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Don Bosco's angel dog: Grigio (1854)

- The purifying flames of Sophie-Thérèse de Soubiran La Louvière (1861)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- Lost for over a century, a Russian icon reappears (1930)

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- He should have died of hypothermia in Soviet jails (1972)

- God protects a secret agent (1975)

- Flowing lava stops at church doors (1977)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- The miracles of Saint Juliana of Nicomedia (1994)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- The providential finding of the Mary of Nazareth International Center's future site (2000)

- Syrian Monastery shielded from danger multiple times (2011-2020)

- Jesus

- Who are we?

- Make a donation

EVERY REASON TO BELIEVE

Les papes

n°272

Rome

540 - 604

Saint Gregory the Great, role model for popes

Gregory was born around 540 into a wealthy patrician and Christian family. Around 574-575, he abandoned his position as a high-ranking civil servant for the monastic life. He reluctantly was chosen as successor to Pope Pelagius in 590. Once in office, his genius as a reformer was brilliantly revealed. He was a prolific writer and wrote numerous books on pastoral, liturgical and moral topics, encouraging first of all a change in morals to pastor souls. His founding of monasteries under the rule of Saint Benedict was a great help: the monastic ideal encouraged all Christians, clerics and lay people alike, to follow Christ. Gregory defended the freedom of the Church against the encroachments of the secular power. In a prophetic move, he called for a christiana respublica (a Christian state), which the Carolingian Empire would eventuallty achieve, but his primary intention was to facilitate the expansion of the universal Church, where all peoples would follow Christ. To this end, he sent missionaries to England, and hoped to enlist the help of the Franks in Gaul to evangelise the Germans. His death on 12 March 604 established him as a model for popes.

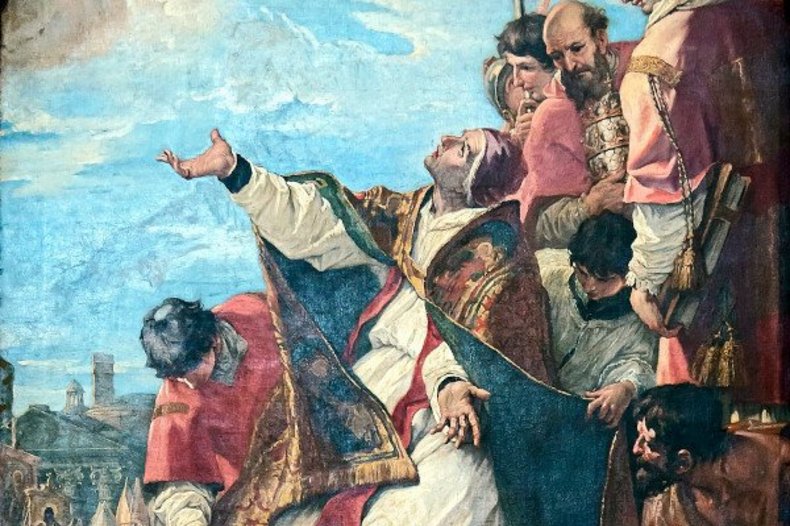

Sebastiano Ricci, Saint Gregory the Great intercedes with Our Lady for the end of the plague in Rome, 1700, Basilica of Santa Justina in Padua / © CC0, wikimedia.

Reasons to believe:

- After receiving an excellent education, Gregory became prefect of the city of Rome in 572. But at the age of 35, he realised that this wordly position did not fulfill his heart nor could it fix the scope of human miseries. Moved by grace, he renounced the honours and riches of the world for a life of prayer and poverty.

- Gregory transformed his family home on Mount Caelius into a monastery (in all, he funded the creation of seven monasteries in Sicily thanks to the fortune he had inherited). He did not head the monastery, but placed himself under the direction of the monk Valentinus, whom he appointed abbot. He bequeathed his remaining possessions to the poor. These elements are the sign of a genuine vocation.

- When he was elected pope in 590, he tried to decline the office, not wanting to abandon the humility of the monastic state.

- The great work carried out by Saint Gregory after his accession to the See of Saint Peter was the reform of the Church. This undertaking alone is enough to show not only Gregory's detachment from the goods of this world, but also his supernatural aim: he had to face many material and human obstacles, when it would have been easy to keep the status quo. A man would not face so many troubles if he were not guided by a higher purpose.

- It is significant that Saint Gregory spent the last six years of his life bedridden because of his health: it was from his bedroom that he carried out his great reforms.

- Based on the spiritual heritage of Saint Benedict, Saint Gregory wrote a collection of four books of miracles, signs, wonders, and healings done by the holy men of sixth-century Italy called the Dialogues (593), the second volume being devoted to the life and rule of Saint Benedict. In this way, he was instrumental in establishing the monastic model that was soon to be followed throughout the West. The fact that so many people voluntarily choose to live according to this rule, even today, reveals its extraordinary depth and the truths it contains about God and mankind.

- Saint Gregory left a large number of writings: he wrote the Pastoral Rule (590), which reiterates the primacy of the care of souls; he also published commentaries on Sacred Scripture (Exposition on Job, 579) and Homilies on the Gospel. No man would expend so much energy if he did not believe in the Saviour he preached about, or if he did not love him and want other men to know that love.

- Saint Gregory is considered to be one of the one of the four Great Latin Church Fathers, and is a Doctor of the Church, that is to say, one of the ecclesiastical writers remarkable for the perfection of their doctrine, authenticated by the sanctity of their lives, and who have particularly contributed to the development of the theological doctrine of the Church.

Summary:

Gregory was born in Rome around 540. He came from a wealthy patrician and Christian family: his father, Gordianus, served as a senator and for a time was the Prefect of the City of Rome; he also held the position of regionarius in the Church. His mother, Sylvia, and two of his aunts, Trasilla and Emiliana, were honoured as saints. Felix III, pope from 483 to 492, was his great-great-grandfather.

The Pragmatic Sanction, issued by Justinian at the request of Pope Vigilius in 554, at the end of the Gothic War, brought Italy back under the direct rule of the Empire and produced a cultural revival. It was in this context that the young Gregory grew up. Gregory of Tours, in his History of the Franks (X, 1), reports that as a student Gregory excelled in grammar, rhetoric, the sciences, literature, and law and that "in grammar, dialectic and rhetoric (the trivium)... he was second to none".

Appointed prefect of Rome in 572, Gregory was highly skilled at managing property at the service of the state. It was also an opportunity for him to learn about the workings of public administration. He also reorganised the Church's properties in the Italian peninsula, which had been under threat since the beginning of the 5th century.

In 574-575, Gregory transformed his family home on Mount Caelius into a monastery and placed himself under the direction of the monk Valentinus, whom he appointed abbot. This was the seventh monastery he built and endowed: six others had already been established in Sicily thanks to the property inherited from his father. Gregory kept nothing for himself: the rest of his fortune was distributed to the poor (History of the Franks, ibid.). It is likely that Gregory chose the rule of Saint Benedict to govern the foundation: the Dialogues (III) show that he held it in high esteem.

Pope Pelagius II sent him to the imperial court in Constantinople as an apocrisiary (ambassador): there he explained to the emperor the dangers of the Lombard invasion of Italy. He remained in Constantinople with a few brothers from his monastery until 586. On his return to Rome, Pope Pelagius appointed him as deacon for the seventh region of Rome (The City was divided into seven districts): Gregory assisted the pontiff until the plague, which was about to strike the city hard, took Pelagius's life in 590. The clergy and people then acclaimed Gregory as the successor to Pope Pelagius. But Gregory did not want to leave the humility of the monastic state.

Events, according to Gregory of Tours, decided otherwise: "He made every effort to avoid this honour, lest, by acquiring such a dignity, he fall back into the vanities of the world, which he had rejected. He therefore wrote to the emperor Maurice, whose son he had baptised in the sacred font, imploring him and asking him with many prayers not to give the people their consent to elevate him to the honours of this rank; but Germanus, prefect of the city of Rome, anticipated Gregory's messenger and, having stopped him, tore up the letters, and sent the emperor the deed of appointment made by the people. Maurice, who loved the deacon Gregory, thanked God for this opportunity to elevate him to dignity, and sent his state letter of recommendation to have him crowned " (History of the Franks, ibid.).

In the meantime, Gregory tried to coordinate relief efforts after the Tiber flooded Rome, destroying the city's grain houses and killing animals. As deacon of one of Rome's ecclesiastical regions, he was responsible for the material aspects of worship in the basilica of the region to which he belonged, as well as raising money for the poor. Now, the seventh ecclesiastical region corresponded to the fourteenth civil region inherited from Augustus' administrative division of the city - the one located trans Tiberim, beyond the river. Judging that only prayer could overcome the disaster, Gregory organised religious processions in each of the regions to pray for God's mercy and help. For three days, choirs went through the streets every three hours, chanting "Kyrie eleison" ("Lord, have mercy!") and calling the people to prayer in the churches.

After six months' vacancy of the episcopal see, Gregory, who had sought to keep a low profile and avoid been elected, was nevertheless led to St Peter's Basilica to receive the consecration on 3 September 590.

The new pontiff set about an administrative reform that prioritised rural populations. He reorganised the assets of the churches of the West, in particular that of Saint Peter, made up of possessions scattered throughout Italy, which the Lombard occupation had dismembered and ruined. This rigorous management enabled him to help the sick and needy in Rome during the famines that raged from 589 to 594, then in 600 and again in 604: he distributed bread, wine and meat, housed refugees driven out by the Lombards, who were moving south, and bought back prisoners. After the Lombards invaded the peninsula, the bishop of Rome had usually assumed the duties of the emperor, since the latter, busy defending the borders of Syria and the Danube, sent very few troops and subsidies to help defend Italy.

Saint Gregory was also at the origin of a reform movement that bore his name and would be extended and imposed on Charlemagne's Christian Europe by the emperor's adviser and friend, the monk Alcuin of York. Gregory's aim was twofold: to bring the clergy back to regular morals, which would in turn encourage the reform of morals throughout society; and to propose standards in both the theological and liturgical fields.

In order to bring about a reform of morals, in 590 Gregory sent John IV, archbishop of Ravenna, a treatise describing the duties of the shepherd of souls: the Pastoral Rule. In four books, the Pope explained that the care of souls is the art of all arts, and that the shepherd of souls should prefer no other. Wasn't this the purpose of his vocation? He needed (and needs) three virtues: discretion, compassion and humility; in this way, everyone, shepherd and sheep alike, will reach the port of salvation that is Paradise. The Pope also enjoined preachers to adapt their sermons to the audience. The Pastoral Rule was translated into Greek by the Patriarch of Antioch at the request of Maurice, Byzantine emperor from 582 to 602. In the 8th century, Alcuin, head of the Palatine School of Aachen - the largest school in the empire - would present the work as a manual for bishops and preachers. Saint Augustine of Canterbury took it with him when Gregory sent him to evangelise England in 597.

Gregory also wrote the Dialogues in 593-594, which he initially intended for monks. However, everyone could benefit from them: the monastic life Gregory had experienced in the Abbey of Saint Andrew, on Mount Caelius in Rome, was for him the model on which clerics - laymen and kings alike - could base their own. In this work, Gregory condemns simony (the buying and selling of spiritual goods) and Nicolaism (the failure of religious and clerics to observe chastity). He refused to allow the laity to interfere in the government of the Church, and insisted on respect for the hierarchy. The human soul is immortal, and to see God after the death of the body is its good: so the Pope urged, through numerous examples of holy people, to work towards this goal on this earth. The Rule of Saint Benedict was a valuable aid in this since it teaches how to live uprightly. Saint Gregory's authority was significant in the subsequent spread of monasteries founded under this rule in the 7th century in Visigothic Spain, Frankish Gaul and Great Britain. The Dialogues were copied, read and applied throughout the Middle Ages.

Saint Gregory also published commentaries on Sacred Scripture. The Book of Job enabled him to present his readers with numerous moral developments. He began his Exposition on Job in Constantinople in 579, when he represented Popes Benedict I and Pelagius II at the imperial court. At the time, these were simply talks for the brothers in his community, written on the spot, and which he supplemented with parts that he dictated. These elements were taken up again and organised in Rome; the work was completed in 595. The Homilies on the Gospel contain the sermons he preached during the first two years of his pontificate (590-592). In addition to the moral teaching that was so dear to him, there was a mystical exposition of the sacred text, in a simple and popular form intended to be received by everyone. In the Homilies on Ezekiel, around 593, he extensively expounds the spiritual meaning of the sacred text: it is this latter meaning that takes precedence because, while it is verified because it is based on the literal meaning - and it is only on this condition that it is admissible - it points to Heaven. Is this not the intention of the sacred author? Other commentaries by the holy pope were written using the same method. Unfortunately, they have been lost.

His works are part of a Christian pedagogy that aimed to teach grammar, dialectics and rhetoric (the trivium of the liberal arts that teaches how to speak clearly, eloquently, and persuasively) by drawing its examples not from secular works, but from the texts of Sacred Scripture. In his Confessions (I, XIII, 20), Saint Augustine lamented the fact that he had learned syntax from the Latin poets of antiquity, whose stories were no more than fables, rather than from the truth of Revelation, which is the written word of God: the pontifical office that Saint Gregory received enabled him to lay the theoretical foundations of a teaching system that Alcuin would later establish in practice throughout the Carolingian Empire.

Finally, Gregory was also a liturgical reformer. His Book of the Sacraments organised the Sacramentary of Pope Gelasius, which set out the liturgy of the Mass and the sacraments, in a different way. The original version has been lost, and the text we know today is the one that Pope Adrian I sent to Charlemagne, around 785-786. The Gregorian Antiphonary, a book of choral music to be sung antiphonally in services, is traditionally attributed to him. John the Deacon (d. c. 882) ascribed to Gregory I the compilation of the books of music used by the schola cantorum established at Rome, by that same pope. Gregorian chant, the central tradition of Western plainchant, while not invented by Gregory the Great, developed in the 9th and 10th centuries probably because of his vision and efforts in promoting this form of sacred singing used in liturgical worship.

His negotiations with the Arian Lombard king Agilulf were facilitated by the help of Agilulf's Catholic wife, Theodelinda of Bavaria. The latter gradually converted her husband to the faith of the Council of Nicaea (i.e. the Catholic faith), and eventually the king had his young son Adaloald baptised in 603. Some Lombard lords followed his example. Monza Cathedral preserves a cross made of rock crystal and gold that Gregory, then a deacon, presented to the queen.

In Gaul, Gregory deplored the practice of simony, which was undermining the dioceses. He first urged Brunehaut and her son Childebert, then Thierry II and Theudebert, her grandsons, to suppress these abuses in agreement with the bishops. He hoped that the Franks of Gaul would assist in evangelising the Germans, since the emperor Maurice had abandoned them to their paganism.

It was through English missionaries that Gregory succeeded - posthumously. The kingdom of the Angles was pagan, due to the Saxons who inhabited it, when the future Saint Augustine of Canterbury arrived there in 596 with forty monks from the monastery of Mount Caelius. They had been sent by Pope Gregory to restore Catholicism. Carried out with tact, prudence, selflessness, and a great supernatural spirit, the undertaking succeeded beyond all expectations , since 120 years later, under Pope Gregory II, Wynfrid of Wessex, better known as Saint Boniface of Mainz, set about evangelising Germania beyond the Rhine before leaving, once the dioceses had been founded, to proclaim Christ the Saviour in Friesland.

It is therefore not surprising that the first biographer of Saint Gregory, probably between 704 and 714, was an Englishman, a monk from the great abbey of Whitby in Northumbria, nor that Paul the Deacon, who wrote the second Life, was inspired by the Ecclesiastical History of the English People by Saint Bede the Venerable, a monk from the abbey of Jarrow in Northumbria (near the present-day town of Sunderland). Alfred, king of Wessex (in the far south of present-day England) from 871 until his death and, from 886, "king of the Anglo-Saxons", who worked to revive teaching and education after the ruin left in his country by the Danish invasions, translated the Pastoral Rule into the vernacular (West Saxon) and commissioned Werferth, Bishop of Worcester, to translate the Dialogues. It is interesting to note the parallels between the cultural revival of this period in England and that sought by the Emperor Justinian after his reconquest of Italy from the Ostrogoths, and that Saint Gregory played a role in both.

Fr. Vincent-Marie Thomas, Ph. D. in Philosophy

Going further:

In the Eye of the Storm: A Biography of Gregory the Great by Sigrid Grabner, Ignatius Press; First Edition (November 30, 2021)

More information:St. Gregory the Great: Biography, Selected Epistles and Teachings on the Pastoral Rule by Kyler M. Kauth, Independently published (January 21, 2024)

St Gregory the Great: Dialogues (Fathers of the Church) by Gregory the Great (Author), Odo John Zimmerman (Translator), The Catholic University of America Press (July 13, 2002)

The Book of Pastoral Rule: St. Gregory the Great (Popular Patristics Series) by Pope Gregory I (Author), George E. Demacopoulos (Translator), St Vladimirs Seminary Pr (January 5, 2007)

Saint Gregory the Great Collection: 3 Books, Aeterna Press (October 6, 2016) - 544 p

The Life of St. Benedict by Gregory the Great: Translation and Commentary by Terrence G. Kardong OSB, Liturgical Press (March 1, 2009)

St. Gregory the Great: Biography, Selected Epistles and Teachings on the Pastoral Rule by Kyler M. Kauth, Independently published (January 21, 2024)

St Gregory the Great: Dialogues (Fathers of the Church) by Gregory the Great (Author), Odo John Zimmerman (Translator), The Catholic University of America Press (July 13, 2002)

The Book of Pastoral Rule: St. Gregory the Great (Popular Patristics Series) by Pope Gregory I (Author), George E. Demacopoulos (Translator), St Vladimirs Seminary Pr (January 5, 2007)

Saint Gregory the Great Collection: 3 Books, Aeterna Press (October 6, 2016) - 544 p

The Life of St. Benedict by Gregory the Great: Translation and Commentary by Terrence G. Kardong OSB, Liturgical Press (March 1, 2009)