- By theme

- Jesus

- The many proofs of Christ’s resurrection

- Saint Thomas Aquinas: God gave all the divine proofs we needed to believe

- The surpassing power of Christ's word

- Lewis’s trilemma: a proof of Jesus’s divinity

- God saves: the power of the holy name of Jesus

- Jesus spoke and acted as God's equal

- Jesus' divinity is actually implied in the Koran

- Jesus came at the perfect time of history

- Rabbinical sources testify to Jesus' miracles

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- The martyrs

- The protomartyr Saint Stephen (d. 31)

- Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, disciple of John and martyr (d. 155)

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Agatha stops a volcano from destroying the city of Catania (d. 251)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The martyrdom of Paul Miki and his companions (d. 1597)

- The martyrs of Angers and Avrillé (1794)

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- He braved torture to atone for his apostasy (d. 1818)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

- José Luis Sanchez del Rio, martyred at age 14 for Christ the King (d. 1928)

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- Saint Anthony of the Desert, a father of monasticism (d. 356)

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The surprising death of Father Emmanuel de Floris (d. 1992)

- The prophecies of Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (d. 1994)

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

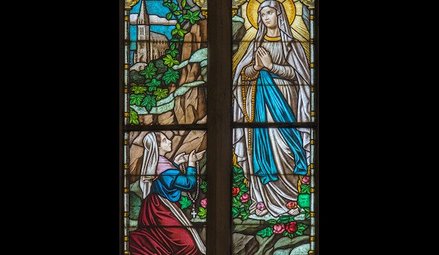

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Rose of Viterbo or How prayer can transform the world (d. 1252)

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence (d. 1317)

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

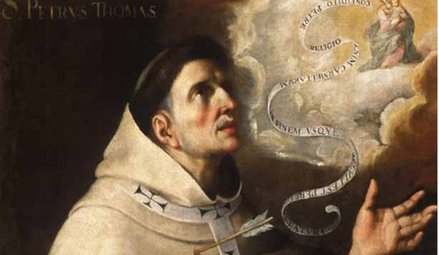

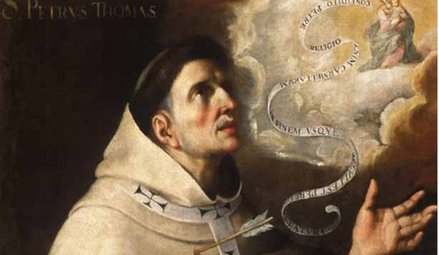

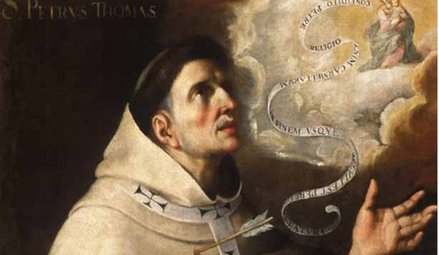

- Saint Peter Thomas (d. 1366): a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love (d. 1510)

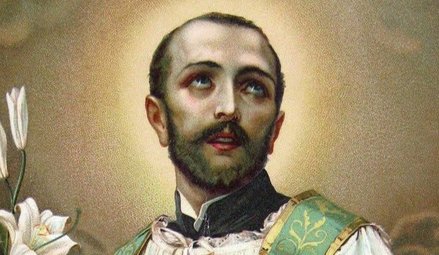

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833): the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

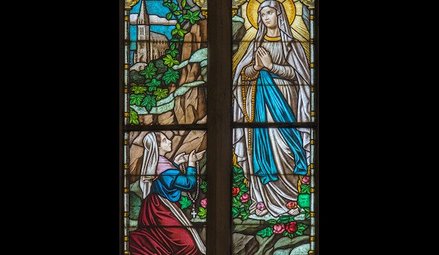

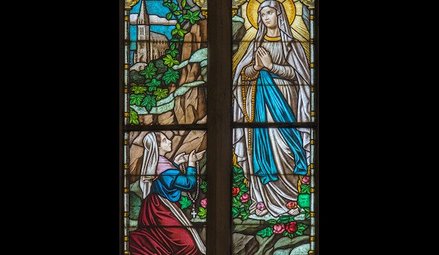

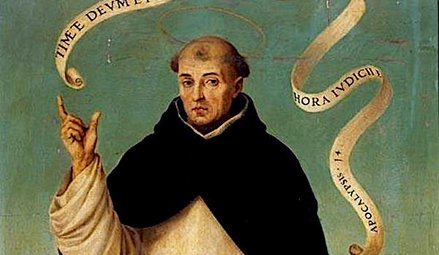

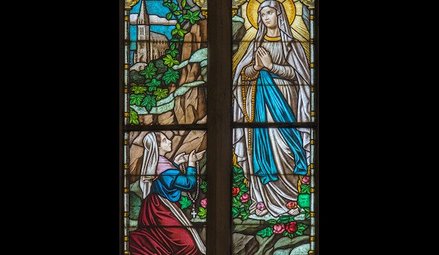

- Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary (1858)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin" (d. 1862)

- Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble (1863)

- Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church (d. 1872)

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God” (d. 1919)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Lutgardis of Tongeren and the devotion to the Sacred Heart

- Saint Angela of Foligno (d. 1309) and "Lady Poverty"

- Saint John of the Cross: mystic, reformer, poet, and universal psychologist (+1591)

- Blessed Anne of Jesus: a Carmelite nun with mystical gifts (d.1621)

- Catherine Daniélou: a mystical bride of Christ in Brittany

- Saint Margaret Mary sees the "Heart that so loved mankind"

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée of Jesus' predictions concerning the Second World War (1922)

- Sister Josefa Menendez, apostle of divine mercy (d. 1923)

- Edith Royer (d. 1924) and the Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre

- Rozalia Celak, a mystic with a very special mission (d. 1944)

- Visionaries

- Saint Perpetua delivers her brother from Purgatory (203)

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Discovery of the Virgin Mary's house in Ephesus (1891)

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- Maria Valtorta's visions match data from the Israel Meteorological Service (1943)

- Berthe Petit's prophecies about the two world wars (d. 1943)

- Maria Valtorta saw only one pyramid at Giza in her visions... and she was right! (1944)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Saint Augustine's conversion: "Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?" (386)

- Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534): a life in service of the truth

- Madame Acarie, "the servant of the servants of God" (d. 1618)

- Blaise Pascal (d.1662): Biblical prophecies are evidence

- Jacinta, 10, offers her suffering to save souls from hell (d. 1920)

- Father Jean-Édouard Lamy: "another Curé of Ars" (d. 1931)

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- The Christian faith explains the diversity of religions

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Our Lady of Virtues saves the city of Rennes in Bretagne (1357)

- Mary stops the plague epidemic at Mount Berico (1426)

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- Savona: supernatural origin of the devotion to Our Lady of Mercy (1536)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- The “aldermen's vow”, or the Marian devotion of the people of Lyon (1643)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- Heaven confides in a shepherdess of Le Laus (1664-1718)

- Zeitoun, a two-year miracle (1968-1970)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- "Our Lady of the Poor" appears eight times in Banneux (1933)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Seuca, Romania: apparitions and pleas of the Virgin Mary, "Queen of Light" (1995)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Mont Saint-Michel: Heaven watching over France

- Angels give a supernatural belt to the chaste Thomas Aquinas (1243)

- The constant presence of demons and angels in the life of St Frances of Rome (d. 1440)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée escapes from prison with the help of an angel (1943)

- Saved by Angels: The Miracle on Highway 6 (2008)

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Angela Merici: Christ came to serve, not to be served (d. 1540)

- Saint John of God: a life dedicated to the care of the poor, sick and those with mental disorders (d. 1550)

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Blessed Alix Le Clerc, encouraged by the Virgin Mary to found schools (d. 1622)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montreal's first teacher (d. 1700)

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Damian of Molokai: a leper for Christ (d. 1889)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Saint Dulce of the Poor, the Good Angel of Bahia (d. 1992)

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- The miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua (d. 1231)

- Saint Philip Neri calls a teenager back to life (1583)

- Saint Francis de Sales brings back to life a victim of drowning (1623)

- Saint John Bosco and the promise kept beyond the grave (1839)

- The day the sun danced at Fatima (1917)

- Pius XII and the miracle of the sun at the Vatican (1950)

- When Blessed Charles de Foucauld saved a young carpenter named Charle (2016)

- Reinhard Bonnke: 89 million conversions (d. 2019)

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Our Lady at Pellevoisin: "I am all merciful" (1876)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- Gemma Galgani: healed to atone for sinners' faults (d. 1903)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The extraordinary healing of Alice Benlian in the Church of the Holy Cross in Damascus (1983)

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Healed by St Charbel Makhlouf, her scars bleed each month for the benefit of unbelievers (1993)

- The miracle that led to Brother André's canonisation (1999)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Dying in the odour of sanctity

- The body of Saint Cecilia found incorrupt (d. 230)

- Stanislaus Kostka's burning love for God (d. 1568)

- Blessed Antonio Franco, bishop and defender of the poor (d. 1626)

- The incorrupt body of Marie-Louise Nerbollier, the visionary from Diémoz (d. 1910)

- The great exhumation of Saint Charbel (1950)

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Saidnaya icon exudes a wonderful fragrance (1988)

- Our Lady weeps in a bishop's hands (1995)

- Stigmates

- The venerable Lukarda of Oberweimar shares her spiritual riches with her convent (d. 1309)

- Blessed Maria Grazia Tarallo, mystic and stigmatist (d. 1912)

- Saint Padre Pio: crucified by Love (1918)

- Elena Aiello: "a Eucharistic soul"

- A Holy Triduum with a Syrian mystic, witnessing the sufferings of Christ (1987)

- A Holy Thursday in Soufanieh (2004)

- Eucharistic miracles

- Lanciano: the first and possibly the greatest Eucharistic miracle (750)

- A host came to her: 11-year-old Imelda received Communion and died in ecstasy (1333)

- Faverney's hosts miraculously saved from fire

- A tsunami recedes before the Blessed Sacrament (1906)

- Buenos Aires miraculous host sent to forensic lab, found to be heart muscle (1996)

- Relics

- The Veil of Veronica, known as the Manoppello Image

- For centuries, the Shroud of Turin was the only negative image in the world

- The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

- Saint Louis (d. 1270) and the relics of the Passion

- The miraculous rescue of the Shroud of Turin (1997)

- A comparative study of the blood present in Christ's relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Francis Xavier Samson Libermann, Jewish convert to Catholicism (1824)

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal and the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne (1842)

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- The conversion of an executioner during the Terror (1830)

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- Dazzled by God: Madeleine Delbrêl's story (1924)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Nelly Gillant: from Reiki Master to Disciple of Christ (2018)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Jesus audibly calls Alphonsus Liguori to follow him (1723)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Alicja Lenczewska: conversations with Jesus (1985)

- Vassula Ryden and the "True Life in God" (1985)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Invited to the celestial court: the story of Chantal (2017)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- Seven golden stars reveal the future location of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery (1132)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- A celestial music comforts Elisabetta Picenardi on her deathbed (d. 1468)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- The strange adventure of Yves Nicolazic (1623)

- Julien Maunoir miraculously learns Breton (1626)

- Pierre de Keriolet: with Mary, one cannot be lost (1636)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Don Bosco's angel dog: Grigio (1854)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- Lost for over a century, a Russian icon reappears (1930)

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- He should have died of hypothermia in Soviet jails (1972)

- God protects a secret agent (1975)

- Flowing lava stops at church doors (1977)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- The miracles of Saint Juliana of Nicomedia (1994)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- Syrian Monastery shielded from danger multiple times (2011-2020)

- Jesus

- Who are we?

- Make a donation

< Toutes les raisons sont ici !

TOUTES LES RAISONS DE CROIRE

- Jesus

- The many proofs of Christ’s resurrection

- Saint Thomas Aquinas: God gave all the divine proofs we needed to believe

- The surpassing power of Christ's word

- Lewis’s trilemma: a proof of Jesus’s divinity

- God saves: the power of the holy name of Jesus

- Jesus spoke and acted as God's equal

- Jesus' divinity is actually implied in the Koran

- Jesus came at the perfect time of history

- Rabbinical sources testify to Jesus' miracles

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- The martyrs

- The protomartyr Saint Stephen (d. 31)

- Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, disciple of John and martyr (d. 155)

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Agatha stops a volcano from destroying the city of Catania (d. 251)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The martyrdom of Paul Miki and his companions (d. 1597)

- The martyrs of Angers and Avrillé (1794)

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- He braved torture to atone for his apostasy (d. 1818)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

- José Luis Sanchez del Rio, martyred at age 14 for Christ the King (d. 1928)

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- Saint Anthony of the Desert, a father of monasticism (d. 356)

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The surprising death of Father Emmanuel de Floris (d. 1992)

- The prophecies of Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (d. 1994)

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Rose of Viterbo or How prayer can transform the world (d. 1252)

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence (d. 1317)

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

- Saint Peter Thomas (d. 1366): a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love (d. 1510)

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833): the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

- Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary (1858)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin" (d. 1862)

- Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble (1863)

- Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church (d. 1872)

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God” (d. 1919)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Lutgardis of Tongeren and the devotion to the Sacred Heart

- Saint Angela of Foligno (d. 1309) and "Lady Poverty"

- Saint John of the Cross: mystic, reformer, poet, and universal psychologist (+1591)

- Blessed Anne of Jesus: a Carmelite nun with mystical gifts (d.1621)

- Catherine Daniélou: a mystical bride of Christ in Brittany

- Saint Margaret Mary sees the "Heart that so loved mankind"

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée of Jesus' predictions concerning the Second World War (1922)

- Sister Josefa Menendez, apostle of divine mercy (d. 1923)

- Edith Royer (d. 1924) and the Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre

- Rozalia Celak, a mystic with a very special mission (d. 1944)

- Visionaries

- Saint Perpetua delivers her brother from Purgatory (203)

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Discovery of the Virgin Mary's house in Ephesus (1891)

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- Maria Valtorta's visions match data from the Israel Meteorological Service (1943)

- Berthe Petit's prophecies about the two world wars (d. 1943)

- Maria Valtorta saw only one pyramid at Giza in her visions... and she was right! (1944)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Saint Augustine's conversion: "Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?" (386)

- Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534): a life in service of the truth

- Madame Acarie, "the servant of the servants of God" (d. 1618)

- Blaise Pascal (d.1662): Biblical prophecies are evidence

- Jacinta, 10, offers her suffering to save souls from hell (d. 1920)

- Father Jean-Édouard Lamy: "another Curé of Ars" (d. 1931)

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- The Christian faith explains the diversity of religions

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Our Lady of Virtues saves the city of Rennes in Bretagne (1357)

- Mary stops the plague epidemic at Mount Berico (1426)

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- Savona: supernatural origin of the devotion to Our Lady of Mercy (1536)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- The “aldermen's vow”, or the Marian devotion of the people of Lyon (1643)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- Heaven confides in a shepherdess of Le Laus (1664-1718)

- Zeitoun, a two-year miracle (1968-1970)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- "Our Lady of the Poor" appears eight times in Banneux (1933)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Seuca, Romania: apparitions and pleas of the Virgin Mary, "Queen of Light" (1995)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Mont Saint-Michel: Heaven watching over France

- Angels give a supernatural belt to the chaste Thomas Aquinas (1243)

- The constant presence of demons and angels in the life of St Frances of Rome (d. 1440)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée escapes from prison with the help of an angel (1943)

- Saved by Angels: The Miracle on Highway 6 (2008)

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Angela Merici: Christ came to serve, not to be served (d. 1540)

- Saint John of God: a life dedicated to the care of the poor, sick and those with mental disorders (d. 1550)

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Blessed Alix Le Clerc, encouraged by the Virgin Mary to found schools (d. 1622)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montreal's first teacher (d. 1700)

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Damian of Molokai: a leper for Christ (d. 1889)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Saint Dulce of the Poor, the Good Angel of Bahia (d. 1992)

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- The miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua (d. 1231)

- Saint Philip Neri calls a teenager back to life (1583)

- Saint Francis de Sales brings back to life a victim of drowning (1623)

- Saint John Bosco and the promise kept beyond the grave (1839)

- The day the sun danced at Fatima (1917)

- Pius XII and the miracle of the sun at the Vatican (1950)

- When Blessed Charles de Foucauld saved a young carpenter named Charle (2016)

- Reinhard Bonnke: 89 million conversions (d. 2019)

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Our Lady at Pellevoisin: "I am all merciful" (1876)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- Gemma Galgani: healed to atone for sinners' faults (d. 1903)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The extraordinary healing of Alice Benlian in the Church of the Holy Cross in Damascus (1983)

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Healed by St Charbel Makhlouf, her scars bleed each month for the benefit of unbelievers (1993)

- The miracle that led to Brother André's canonisation (1999)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Dying in the odour of sanctity

- The body of Saint Cecilia found incorrupt (d. 230)

- Stanislaus Kostka's burning love for God (d. 1568)

- Blessed Antonio Franco, bishop and defender of the poor (d. 1626)

- The incorrupt body of Marie-Louise Nerbollier, the visionary from Diémoz (d. 1910)

- The great exhumation of Saint Charbel (1950)

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Saidnaya icon exudes a wonderful fragrance (1988)

- Our Lady weeps in a bishop's hands (1995)

- Stigmates

- The venerable Lukarda of Oberweimar shares her spiritual riches with her convent (d. 1309)

- Blessed Maria Grazia Tarallo, mystic and stigmatist (d. 1912)

- Saint Padre Pio: crucified by Love (1918)

- Elena Aiello: "a Eucharistic soul"

- A Holy Triduum with a Syrian mystic, witnessing the sufferings of Christ (1987)

- A Holy Thursday in Soufanieh (2004)

- Eucharistic miracles

- Lanciano: the first and possibly the greatest Eucharistic miracle (750)

- A host came to her: 11-year-old Imelda received Communion and died in ecstasy (1333)

- Faverney's hosts miraculously saved from fire

- A tsunami recedes before the Blessed Sacrament (1906)

- Buenos Aires miraculous host sent to forensic lab, found to be heart muscle (1996)

- Relics

- The Veil of Veronica, known as the Manoppello Image

- For centuries, the Shroud of Turin was the only negative image in the world

- The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

- Saint Louis (d. 1270) and the relics of the Passion

- The miraculous rescue of the Shroud of Turin (1997)

- A comparative study of the blood present in Christ's relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Francis Xavier Samson Libermann, Jewish convert to Catholicism (1824)

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal and the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne (1842)

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- The conversion of an executioner during the Terror (1830)

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- Dazzled by God: Madeleine Delbrêl's story (1924)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Nelly Gillant: from Reiki Master to Disciple of Christ (2018)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Jesus audibly calls Alphonsus Liguori to follow him (1723)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Alicja Lenczewska: conversations with Jesus (1985)

- Vassula Ryden and the "True Life in God" (1985)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Invited to the celestial court: the story of Chantal (2017)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- Seven golden stars reveal the future location of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery (1132)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- A celestial music comforts Elisabetta Picenardi on her deathbed (d. 1468)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- The strange adventure of Yves Nicolazic (1623)

- Julien Maunoir miraculously learns Breton (1626)

- Pierre de Keriolet: with Mary, one cannot be lost (1636)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Don Bosco's angel dog: Grigio (1854)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- Lost for over a century, a Russian icon reappears (1930)

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- He should have died of hypothermia in Soviet jails (1972)

- God protects a secret agent (1975)

- Flowing lava stops at church doors (1977)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- The miracles of Saint Juliana of Nicomedia (1994)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- Syrian Monastery shielded from danger multiple times (2011-2020)

Les saints

n°78

Gaul

395-479

Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns

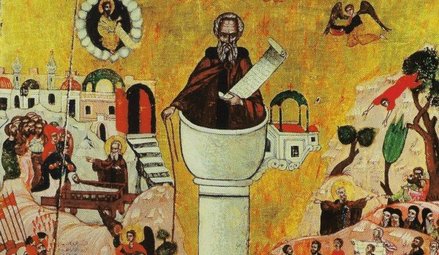

While still a young man, Lupus gave up all his wealth and parted from his wife by mutual agreement to become a monk. He eventually came to the attention of Germanus of Auxerre, who appointed him bishop of Troyes. Lupus at first declined, but eventually relented. Then, he accompanied Germanus to Britain to preach against Pelagianism. Back in Gaul, he defended his city against Attila's army and, offering himself voluntarily as a hostage, managed to escort the "scourge of God" back to the Rhine. This feat, along with the many miracles that accompanied his life, quickly earned him a reputation for sanctity.

Saint Loup saving the town of Troyes from Attila's Huns in 451, Saint-Pierre Saint-Paul church, Épernay / CC BY-SA 3.0/G. Garitan

Les raisons d'y croire :

- The life of Saint Lupus is attested by reliable historical sources, including a letter written by him in 454. The famous Sidonius Apollinaris (poet, diplomat, and bishop), who was Lupus' contemporary, also mentions him in a number of letters. Historians also consider that his hagiography, the Vita Lupi, dates from shortly after his death (between 511 and 731). Finally, the Vita Germani (life of his friend Saint Germanus), written thirty years after his death, mentions many of Saint Lupus' deeds.

- Lupus met with Attila and was able to protect the city of Troyes: his intelligence and piety impressed the warlord, renowned for his ferocity and rapacity. Soon after this meeting him, Attila withdrew his troops from Gaul.

- He met the other great and holy figures of his time, Germanus of Auxerre and Genevieve of Nanterre and, with them, continued the evangelization of Gaul.

- He was a participant in the shift of political governance to the Frankish kings in Roman Gaul as the Roman Empire collapsed and witnessed the birth of the Merovingian dynasty.

- Numerous miracles are attributed to him both during his life and after his death: he had hostages released by sending a letter to a barbarian chief; resurrected the son of the great lord Germanicus; exorcised a young girl and delivered her from her muteness; cured a paralytic; saved a slave - who had taken refuge at his tomb - from his master's violence, etc.

Synthèse :

Born into a Gallo-Roman noble family, Lupus (or Leu) was born at the end of the 4th century. The new century (5th c.) was a time of great conflicts and upheavals, resulting the end of the Western Roman Empire (476). Lupus was one of those rare great figure to emerge above this unprecedented chaos and to leave a long legacy, enabling the establishment of a new Christian power in a newly independent Gaul, soon to be known as France.

In the meantime, after studying rhetoric and Latin to become a lawyer, Lupus, son of a wealthy nobleman called Epirocus of Toul, married one of Saint Hilary of Poitiers' sisters, Pimeniola. After seven years together, by mutual agreement husband and wife separated to individually devote their lives to God, and each embraced the monastic life. Lupus entered the Lérins Abbey (on a Mediterranean island off the French Riviera), founded by Saint Honoratus of Arles, a close relative of Hilary - a community renowned for its ascetic rule and the first monastery in the West. But in 426, Lupus retired to Macon where he came to the attention of Germanus of Auxerre, who appointed Lupus the Bishop of Troyes. Or, as another story holds, as he travelled to Macon to sell one of his last possessions, Lupus was "kidnapped" by the inhabitants of Troyes, who elected him bishop against his will, so great was his reputation for holiness.

A few years later, a council appointed him, along with his neighbour Saint Germanus of Auxerre, to go and preach against the Pelagian heresy that was developing in Britain. It was on their way, passing through Nanterre, that they both met the future Saint Genevieve, only ten years old at the time, but whose future destiny they could already foresee. Across the Channel, the two bishops worked wonders, confounding heretics and helping to repel a Saxon invasion. Once his mission was accomplished, Lupus returned to his diocese where - as he did not yet know - a much greater danger awaited him: Attila the Hun had penetrated Gaul, and had sacked Reims, Cambrai, Metz and Auxerre. Defeated at the Catalaunian Plains, near Châlons, by Aetius and a confederation of Germanic peoples, the barbarian ruler had not yet finished wreaking havoc: he was heading for Troyes, whose walls were in ruins and unable to protect the inhabitants. Lupus sent two emissaries to Attila, who derisively killed one of them (the martyr Saint Mesmin) and seriously wounded the other (Camelian, Lupus' future successor as king of Troyes).

However, emboldened by his faith in God, Lupus went to see Attila in person, and it is believed that it was during this meeting that Attila referred to himself as "the scourge of God". The bishop agreed with him on that point, but warned him not to abuse his power. At the end of their talk, the Hun leader spared Troyes and agreed to withdraw to the Rhine region if Lupus accompanied him as a hostage, to protect his troops from attacks. It is said that he would have liked the bishop to follow him further, and that he recommended himself to his prayers. In any case, this miraculous rescue made Lupus famous throughout Gaul. Lupus died while still serving as a bishop, beloved and admired by his people. Shortly after his death, he was raised to the altars. His remains were deposited in the Saint-Loup Abbey in Troyes, which he had founded.

In the city of Troyes, which has always had a great devotion to him, the glory of Saint Loup (as he is known in France) has endured down the centuries. Troyes celebrated an annual festival of the "salted meat", from the 16th to the 18th centuries during Rogations days, with an effigy of a bronze dragon carried around the town, evoking the dragon that Saint Lupus was supposed to have defeated and that was initially preserved by salting its flesh.

Saint Lupus was one of the great bishops who maintained order in Gaul at a time when everything was falling apart, who protected its people, and helped to complete the Christianisation of the country.

Jacques de Guillebon is an essayist and journalist. He is a contributor to the Catholic magazine La Nef.

Au-delà des raisons d'y croire :

Saint Lupus hold an important place among the great saints who helped build France.

Aller plus loin :

The Origin & Development of the Christian Church in Gaul, by Thomas Scott Holmes, Legare Street Press (October 27, 2022)

En savoir plus :- Christianity's Quiet Success: The Eusebius Gallicanus Sermon Collection and the Power of the Church in Late Antique Gaul by Lisa Kaaren Bailey, University of Notre Dame Press; First Edition (November 15, 2010)

Bishops and the Politics of Patronage in Merovingian Gaul, by Gregory I. Halfond, Cornell University Press (September 15, 2019)

St. Germanus of Auxerre, by Howard Huws, Orthodox Logos Foundation (December 21, 2011)

The Western Fathers Being the Lives of Martin of Tours, Ambrose, Augustine of Hippo, Honoratus of Arles and Germanus of Auxerre, by Sulpicius Severus, Paulinus the Deacon, Possidius, Hilary of Arles, Constantius of Lyons, Harper Torchbooks (January 1, 1965)

Bishops and the Politics of Patronage in Merovingian Gaul, by Gregory I. Halfond, Cornell University Press (September 15, 2019)

St. Germanus of Auxerre, by Howard Huws, Orthodox Logos Foundation (December 21, 2011)

The Western Fathers Being the Lives of Martin of Tours, Ambrose, Augustine of Hippo, Honoratus of Arles and Germanus of Auxerre, by Sulpicius Severus, Paulinus the Deacon, Possidius, Hilary of Arles, Constantius of Lyons, Harper Torchbooks (January 1, 1965)

LES RAISONS DE LA SEMAINE

L’Église ,

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Saint Simon Stock reçoit le scapulaire du Mont Carmel des mains de la Vierge Marie

Les saints

Saint Pascal Baylon, humble berger

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Stigmates

Sainte Rita de Cascia, celle qui espère contre toute espérance

Les saints

L’étrange barque de saint Basile de Riazan

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Antoine de Padoue, le « saint que tout le monde aime »

Les saints ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

L’extraordinaire conversion de Micheline de Pesaro

Les saints ,

Les anges et leurs manifestations ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Antoine-Marie Zaccaria, médecin des corps et des âmes

Les saints

Les saints époux Louis et Zélie Martin

Les saints ,

La profondeur de la spiritualité chrétienne

Frère Marcel Van, une « étoile s’est levée en Orient »

Les saints

Sainte Anne et saint Joachim, parents de la Vierge Marie

Les saints

Saint Loup, l’évêque qui fit rebrousser chemin à Attila

Les saints

Saint Ignace de Loyola : à la plus grande gloire de Dieu

Les saints

Saint Nazaire, apôtre et martyre

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Saint Jean-Marie Vianney, la gloire mondiale d’un petit curé de campagne

Les moines ,

Les saints

Saint Dominique de Guzman, athlète de la foi

Les saints ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Sainte Faustine, apôtre de la divine miséricorde

Les moines ,

Lévitations ,

Stigmates ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Saint François, le pauvre d’Assise

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Ignace d’Antioche : successeur des apôtres et témoin de l’Évangile

Les saints

Antoine-Marie Claret, un tisserand devenu ambassadeur du Christ

Les saints

Alphonse Rodriguez, le saint portier jésuite

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Bilocations

Martin de Porrès revient hâter sa béatification

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants

Saint Martin de Tours, père de la France chrétienne

Les saints

Saint Grégoire le Thaumaturge

Les saints ,

Une vague de charité unique au monde ,

Corps conservés des saints

Virginia Centurione Bracelli : quand toutes les difficultés s’aplanissent

Les saints

Lorsque le moine Seraphim contemple le Saint-Esprit

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Pierre Thomas : une confiance en la Vierge Marie à toute épreuve

Les saints

À Grenoble, le « saint abbé Gerin »

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Gabriel de l’Addolorata, le « jardinier de la Sainte Vierge »

Les saints ,

Les mystiques ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Sainte Rose de Viterbe : comment la prière change le monde

Les saints

Bienheureux Francisco Palau y Quer, un amoureux de l’Église

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

La maturité surnaturelle de Francisco Marto, « consolateur de Dieu »

L’Église ,

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

San Simón Stock recibe el escapulario del Carmen de manos de la Virgen María

Les saints

San Pascual Baylon, humilde pastor

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Stigmates

Santa Rita de Casia, la que espera contra toda esperanza

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Bernadette Soubirous, bergère qui vit la Vierge

Les saints ,

Histoires providentielles

L’absolue confiance en Dieu de sainte Agnès de Montepulciano

Les saints

Sainte Catherine de Gênes, ou le feu de l’amour de Dieu

Les saints

Sainte Marie de l’Incarnation, « la sainte Thérèse du Nouveau Monde »

Les saints

Rosa Venerini ou la parfaite volonté de Dieu

L’Église ,

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Saint Simon Stock reçoit le scapulaire du Mont Carmel des mains de la Vierge Marie

Les saints

Saint Paschal Baylón: from humble shepherd to the glory of sainthood

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Stigmates

Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

Les saints

Camille de Soyécourt, comblée par Dieu de la vertu de force

L’Église ,

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

San Simone Stock ricevette dalle mani della Vergine Maria lo scapolare del Monte Carmelo

Les saints

San Pascal Baylon, umile pastore

Les saints

François de Girolamo lit dans les cœurs

Les saints ,

La profondeur de la spiritualité chrétienne

Hermano Marcel Van, "una estrella ha nacido en Oriente".

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Stigmates

Santa Rita da Cascia, colei che spera contro ogni speranza

Les saints

La extraña barca de San Basilio de Riazán

Les saints

Jeanne-Antide Thouret : partout où Dieu voudra l’appeler

Les saints

The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

Les saints ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

San Antonio de Padua, el "santo que todo el mundo ama".

Les saints ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

La extraordinaria conversión de Micheline de Pesaro

Les saints

Saint Augustin de Cantorbéry apporte la bonne nouvelle sur la terre des Angles

Les saints ,

Les anges et leurs manifestations ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls

Les saints ,

La profondeur de la spiritualité chrétienne

Brother Marcel Van: a "star has risen in the East"

Les saints

Saints Louis and Zelie Martin

Les saints

La strana barca di San Basilio di Ryazan

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

Sant'Antonio da Padova, il "santo che tutti amano"

Les saints ,

Les anges et leurs manifestations ,

Corps conservés des saints

San Antonio María Zaccaria, médico de cuerpos y almas

Les saints

Los Santos esposos Luis y Celia Martin

Les saints

Saint Rainer de Pise : la conversion miraculeuse d’un riche négociant

Les saints ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

La straordinaria conversione di Michelina da Pesaro

Les saints

Saint Jean-Baptiste, témoin du Christ annoncé par les prophètes

Les saints ,

Les anges et leurs manifestations ,

Corps conservés des saints

Sant'Antonio Maria Zaccaria, medico del corpo e dell'anima

Les saints

Saint Bernardin Realino répond à l’appel divin

Les saints

Santa Ana y San Joaquín, padres de la Virgen María

Les saints

San Nazario, apóstol y mártir

Les saints

San Lupo, el obispo que hizo retroceder a Atila

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

Sainte Élisabeth du Portugal, une rose en royauté

Les saints

San Ignacio de Loyola: a la mayor gloria de Dios

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

San Juan María Vianney, la gloria mundial de un cura de pueblo

Les moines ,

Les saints

Santo Domingo de Guzmán, atleta de la fe

Les saints ,

La profondeur de la spiritualité chrétienne

Fratel Marcel Van, "una stella è sorta in Oriente"

Les saints

I santi sposi Louis e Zélie Martin

Les saints

Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary

Les saints

La confiance en Dieu de sainte Marie-Madeleine Postel

Les saints

Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr

Les saints

Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns

Les saints

Saint Ignatius of Loyola: "For the greater glory of God"

Les saints

Sant'Anna e San Gioacchino, genitori della Vergine Maria

Les saints

San Nazario, apostolo e martire

Les saints

San Lupo, il vescovo che fece indietreggiare Attila

Les saints

Sant'Ignazio di Loyola: per la maggior gloria di Dio

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

Les moines ,

Les saints

Saint Dominic de Guzman: an athlete of the faith

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

San Giovanni Maria Vianney, la gloria mondiale di un piccolo curato di campagna

Les moines ,

Les saints

San Domenico di Guzmán, atleta della fede

Les saints ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Santa Faustina, apóstol de la Divina Misericordia

Les saints

Jean Eudes, époux du Cœur Immaculé de Marie

Les saints ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy

Les saints

Syméon monte sur une colonne pour demeurer seul avec le Christ

Les saints ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Santa Faustina, apostola della divina misericordia

Les moines ,

Lévitations ,

Stigmates ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi

Les moines ,

Lévitations ,

Stigmates ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

San Francisco, el pobre de Asís

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Ignacio de Antioquía: sucesor de los apóstoles y testigo del Evangelio

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel

Les moines ,

Lévitations ,

Stigmates ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

San Francesco, il poverello d'Assisi

Les saints

Thérèse Couderc remet tout entre les mains de Marie

Les saints

Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy doorkeeper"

Les saints

Alonso Rodríguez, el santo jesuita portero

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Bilocations

Martin de Porrès regresa para acelerar su beatificación

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Bilocations

Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Newman cherche la véritable Église du Christ

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Ignazio di Antiochia: successore degli apostoli e testimone del Vangelo

Les saints

Dieu parle par la bouche de la bienheureuse Madeleine de Panattieri

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants

Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism

Les saints

La « légende » des saints n’est pas un mythe

Les saints

Pierre d’Alcantara, à qui Dieu ne refuse rien

Les saints

Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker

Les saints

Alfonso Rodríguez, il santo portinaio gesuita

Les saints

Hilaire de Mende, un saint évêque thaumaturge

Les saints

Celina Chludzinska, une vie entre les mains de Dieu

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants

San Martín de Tours, padre de la Francia cristiana

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Bilocations

Martín de Porres torna per accelerare la sua beatificazione

Les saints

San Gregorio Taumaturgo

Les saints

Le succès étonnant des prédications de saint Ange d’Acri

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants

San Martino di Tours, padre della Francia cristiana

Les saints

San Gregorio Taumaturgo

Les saints ,

Une vague de charité unique au monde ,

Corps conservés des saints

Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome

Les saints ,

Une vague de charité unique au monde ,

Corps conservés des saints

Virginia Centurione Bracelli: cuando las cosas se ponen difíciles

Les saints

Le mariage virginal de bienheureuse Delphine de Sabran

Les saints

Jacques de la Marche transmet la foi catholique à travers l’Europe

Les saints ,

Une vague de charité unique au monde ,

Corps conservés des saints

Virginia Centurione Bracelli: quando tutte le difficoltà vengono meno

Les saints

Seraphim of Sarov: the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

Les saints ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Née aveugle, sainte Odile retrouve la vue lors de son baptême

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Peter Thomas: a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

Les saints

Cuando el monje Serafín contempla al Espíritu Santo

Les saints

Gatien, apôtre de la Touraine

Les saints

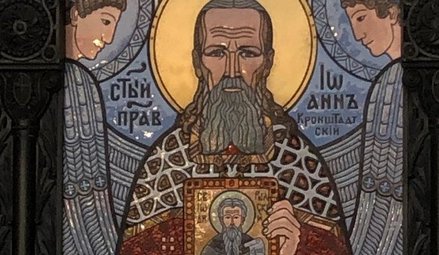

La vie en Jésus Christ de Jean de Cronstadt

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints

San Pedro Tomás: una confianza inquebrantable en la Virgen María

Les saints

Quando il monaco Serafino contemplava lo Spirito Santo

Les saints

La grande conversion de Fabiola

Les saints

Gaspard del Bufalo, le prêtre qui a dit non à Napoléon

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints

San Pietro Tommaso e la sua fiducia incrollabile nella Vergine Maria

Les saints

Mélanie la Jeune : par le chas d’une aiguille

Les saints

Sainte Geneviève, patronne de Paris

Les moines ,

Les saints

Saint André Bessette, serviteur de saint Joseph

Les saints

Saint Remi, l’évêque qui baptisa le roi des Francs

Les saints

Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble

Les saints

Saint Ildefonse de Tolède, défenseur de la Vierge Marie

Les saints

A Grenoble, il "santo abate Gerin"

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin"

Les saints

Saint Avit de Vienne affirme la divinité de Jésus

Les saints

Sainte Joséphine Bakhita, de la souffrance à l’amour

Les saints

En Grenoble, el "santo abate Gerin".

Les saints ,

Les mystiques ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Saint Rose of Viterbo: how prayer changes the world

Les saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Claude La Colombière prédit son emprisonnement

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Gabriel de l'Addolorata, el "jardinero de la Virgen María"

Les saints ,

Les mystiques ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Santa Rosa de Viterbo: cómo la oración cambia el mundo

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Gabriele dell'Addolorata, il "giardiniere della Vergine Maria"

Les saints

Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church

Les saints

Beato Francisco Palau y Quer, amante de la Iglesia

Les saints ,

Les mystiques ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Santa Rosa da Viterbo: come la preghiera cambia il mondo

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

La madurez sobrenatural de Francisco Marto, "consolador de Dios".

Les saints

Le pacte de la comtesse Molé avec la Croix de Jésus-Christ

Les saints

Il beato Francisco Palau y Quer, amante della Chiesa

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God”

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Bernadette Soubirous, la pastora que vio a la Virgen María

Les saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

La maturità soprannaturale di Francisco Marto, "consolatore di Dio"

Les saints

Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love

Les saints

Jeanne-Marie de Maillé traverse les humiliations et la misère accompagnée par la Vierge Marie

Les moines ,

Les saints

Mère Marie Skobtsova, une moniale hors du commun

Les saints

Saint Vincent Ferrier, mirificus praedicator

Les saints ,

Histoires providentielles

La absoluta confianza en Dios de Santa Inés de Montepulciano

Les saints

Santa Catalina de Génova, o el fuego del amor de Dios

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Bernadette Soubirous, la pastorella che vide la Vergine Maria

Les saints

Kateri Tekakwitha, une sainte chez les Mohawks

Les saints ,

Histoires providentielles

La fiducia assoluta in Dio di Sant'Agnese da Montepulciano

Les saints