- By theme

- Jesus

- The many proofs of Christ’s resurrection

- Saint Thomas Aquinas: God gave all the divine proofs we needed to believe

- The surpassing power of Christ's word

- Lewis’s trilemma: a proof of Jesus’s divinity

- God saves: the power of the holy name of Jesus

- Jesus spoke and acted as God's equal

- Jesus' divinity is actually implied in the Koran

- Jesus came at the perfect time of history

- Rabbinical sources testify to Jesus' miracles

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- An enduring prophecy and a series of miraculous events preventing the reconstruction of the Temple

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- Saint Peter, prince of the apostles

- Saint John the Apostle: an Evangelist and Theologian who deserves to be better known (d. 100)

- Saint Matthew, apostle, evangelist and martyr (d. 61)

- James the Just, “brother” of the Lord, apostle and martyr (d. 62 AD)

- Saint Matthias replaces Judas as an apostle (d. 63)

- The martyrs

- The protomartyr Saint Stephen (d. 31)

- Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, disciple of John and martyr (d. 155)

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Agatha stops a volcano from destroying the city of Catania (d. 251)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The martyrdom of Paul Miki and his companions (d. 1597)

- The martyrs of Angers and Avrillé (1794)

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- He braved torture to atone for his apostasy (d. 1818)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

- José Luis Sanchez del Rio, martyred at age 14 for Christ the King (d. 1928)

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- The Desert Fathers (3rd century)

- Saint Anthony of the Desert, a father of monasticism (d. 356)

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The surprising death of Father Emmanuel de Floris (d. 1992)

- The prophecies of Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (d. 1994)

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Rose of Viterbo or How prayer can transform the world (d. 1252)

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence (d. 1317)

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

- Saint Peter Thomas (d. 1366): a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love (d. 1510)

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Saint Marie of the Incarnation, "the Teresa of New France" (d.1672)

- St. Francis di Girolamo's gift of reading hearts and souls (d. 1716)

- Rosa Venerini: moving in the ocean of the Will of God (d. 1728)

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833): the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

- Camille de Soyécourt, filled with divine fortitude (d. 1849)

- Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary (1858)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin" (d. 1862)

- Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble (1863)

- Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church (d. 1872)

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God” (d. 1919)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Lutgardis of Tongeren and the devotion to the Sacred Heart

- Saint Angela of Foligno (d. 1309) and "Lady Poverty"

- Saint John of the Cross: mystic, reformer, poet, and universal psychologist (+1591)

- Blessed Anne of Jesus: a Carmelite nun with mystical gifts (d.1621)

- Catherine Daniélou: a mystical bride of Christ in Brittany

- Saint Margaret Mary sees the "Heart that so loved mankind"

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée of Jesus' predictions concerning the Second World War (1922)

- Sister Josefa Menendez, apostle of divine mercy (d. 1923)

- Edith Royer (d. 1924) and the Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre

- Rozalia Celak, a mystic with a very special mission (d. 1944)

- Visionaries

- Saint Perpetua delivers her brother from Purgatory (203)

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Discovery of the Virgin Mary's house in Ephesus (1891)

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- Maria Valtorta's visions match data from the Israel Meteorological Service (1943)

- Berthe Petit's prophecies about the two world wars (d. 1943)

- Maria Valtorta saw only one pyramid at Giza in her visions... and she was right! (1944)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Saint Augustine's conversion: "Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?" (386)

- Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534): a life in service of the truth

- Madame Acarie, "the servant of the servants of God" (d. 1618)

- Blaise Pascal (d.1662): Biblical prophecies are evidence

- Madame Élisabeth and the sweet smell of virtue (d. 1794)

- Jacinta, 10, offers her suffering to save souls from hell (d. 1920)

- Father Jean-Édouard Lamy: "another Curé of Ars" (d. 1931)

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- The Christian faith explains the diversity of religions

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Our Lady of Virtues saves the city of Rennes in Bretagne (1357)

- Mary stops the plague epidemic at Mount Berico (1426)

- Our Lady of Miracles heals a paralytic in Saronno (1460)

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- Savona: supernatural origin of the devotion to Our Lady of Mercy (1536)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- The “aldermen's vow”, or the Marian devotion of the people of Lyon (1643)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- Heaven confides in a shepherdess of Le Laus (1664-1718)

- Zeitoun, a two-year miracle (1968-1970)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- The five Marian apparitions that traced an "M" over France, and its new pilgrimage route

- A series of Marian apparitions and prophetic messages in Ukraine since the 19th century (1806)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- "Our Lady of the Poor" appears eight times in Banneux (1933)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Mary responds to the Vows of the Polish Nation (1956)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Seuca, Romania: apparitions and pleas of the Virgin Mary, "Queen of Light" (1995)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Mont Saint-Michel: Heaven watching over France

- Angels give a supernatural belt to the chaste Thomas Aquinas (1243)

- The constant presence of demons and angels in the life of St Frances of Rome (d. 1440)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée escapes from prison with the help of an angel (1943)

- Saved by Angels: The Miracle on Highway 6 (2008)

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Peter Nolasco: a life dedicated to ransoming enslaved Christians (d. 1245)

- Saint Angela Merici: Christ came to serve, not to be served (d. 1540)

- Saint John of God: a life dedicated to the care of the poor, sick and those with mental disorders (d. 1550)

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Blessed Alix Le Clerc, encouraged by the Virgin Mary to found schools (d. 1622)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montreal's first teacher (d. 1700)

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Damian of Molokai: a leper for Christ (d. 1889)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Saint Dulce of the Poor, the Good Angel of Bahia (d. 1992)

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- The miracle of liquefaction of the blood of St. Januarius (d. 431)

- The miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua (d. 1231)

- Saint Pius V and the miracle of the Crucifix (1565)

- Saint Philip Neri calls a teenager back to life (1583)

- The resurrection of Jérôme Genin (1623)

- Saint Francis de Sales brings back to life a victim of drowning (1623)

- Saint John Bosco and the promise kept beyond the grave (1839)

- The day the sun danced at Fatima (1917)

- Pius XII and the miracle of the sun at the Vatican (1950)

- When Blessed Charles de Foucauld saved a young carpenter named Charle (2016)

- Reinhard Bonnke: 89 million conversions (d. 2019)

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Our Lady at Pellevoisin: "I am all merciful" (1876)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- Gemma Galgani: healed to atone for sinners' faults (d. 1903)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The extraordinary healing of Alice Benlian in the Church of the Holy Cross in Damascus (1983)

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Healed by St Charbel Makhlouf, her scars bleed each month for the benefit of unbelievers (1993)

- The miracle that led to Brother André's canonisation (1999)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- He had “zero” chance of living: a baby's miraculous recovery (2015)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Dying in the odour of sanctity

- The body of Saint Cecilia found incorrupt (d. 230)

- Stanislaus Kostka's burning love for God (d. 1568)

- Blessed Antonio Franco, bishop and defender of the poor (d. 1626)

- The incorrupt body of Marie-Louise Nerbollier, the visionary from Diémoz (d. 1910)

- The great exhumation of Saint Charbel (1950)

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Saidnaya icon exudes a wonderful fragrance (1988)

- Our Lady weeps in a bishop's hands (1995)

- Stigmates

- The venerable Lukarda of Oberweimar shares her spiritual riches with her convent (d. 1309)

- Florida Cevoli: a heart engraved with the cross (d. 1767)

- Blessed Maria Grazia Tarallo, mystic and stigmatist (d. 1912)

- Saint Padre Pio: crucified by Love (1918)

- Elena Aiello: "a Eucharistic soul"

- A Holy Triduum with a Syrian mystic, witnessing the sufferings of Christ (1987)

- A Holy Thursday in Soufanieh (2004)

- Eucharistic miracles

- Lanciano: the first and possibly the greatest Eucharistic miracle (750)

- A host came to her: 11-year-old Imelda received Communion and died in ecstasy (1333)

- Faverney's hosts miraculously saved from fire

- A tsunami recedes before the Blessed Sacrament (1906)

- Buenos Aires miraculous host sent to forensic lab, found to be heart muscle (1996)

- Relics

- The Veil of Veronica, known as the Manoppello Image

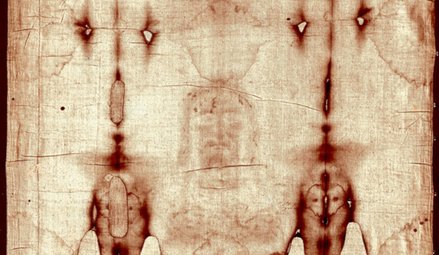

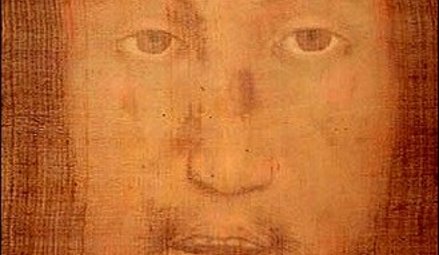

- For centuries, the Shroud of Turin was the only negative image in the world

- The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

- Saint Louis (d. 1270) and the relics of the Passion

- The miraculous rescue of the Shroud of Turin (1997)

- A comparative study of the blood present in Christ's relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Francis Xavier Samson Libermann, Jewish convert to Catholicism (1824)

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal and the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne (1842)

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- The conversion of an executioner during the Terror (1830)

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- Dazzled by God: Madeleine Delbrêl's story (1924)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Nelly Gillant: from Reiki Master to Disciple of Christ (2018)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Jesus audibly calls Alphonsus Liguori to follow him (1723)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Alicja Lenczewska: conversations with Jesus (1985)

- Vassula Ryden and the "True Life in God" (1985)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Invited to the celestial court: the story of Chantal (2017)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- Seven golden stars reveal the future location of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery (1132)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Saint Zita and the miracle of the cloak (13th c.)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- A celestial music comforts Elisabetta Picenardi on her deathbed (d. 1468)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- The strange adventure of Yves Nicolazic (1623)

- Julien Maunoir miraculously learns Breton (1626)

- Pierre de Keriolet: with Mary, one cannot be lost (1636)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- A hundred years before it happened, Saint Andrew Bobola predicted that Poland would be back on the map (1819)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Don Bosco's angel dog: Grigio (1854)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- Lost for over a century, a Russian icon reappears (1930)

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- He should have died of hypothermia in Soviet jails (1972)

- God protects a secret agent (1975)

- Flowing lava stops at church doors (1977)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- The miracles of Saint Juliana of Nicomedia (1994)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- The providential finding of the Mary of Nazareth International Center's future site (2000)

- Syrian Monastery shielded from danger multiple times (2011-2020)

- Jesus

- Who are we?

- Make a donation

TOUTES LES RAISONS DE CROIRE

Reliques

n°90

Argenteuil, France

August 12, 800 AD

The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

For more than 1,200 years, the Basilica of Saint-Denys of Argenteuil, in the northwestern suburbs of Paris, has enshrined a seamless tunic believed to have been the garment worn by Christ Jesus during his passion and carrying of the cross, gambled over by Roman soldiers. It should not be confused with the outer garment of Jesus in the Cathedral of Trier, which was brought from Palestine to Europe by St. Helena (250-330), mother of Emperor Constantine I the Great. In this case, it was Empress Irene of Athens, Empress of the Byzantine Empire (752-802) who presented the tunic to Charlemagne as a coronation gift. The latter entrusted the tunic’s safe-keeping to his daughter, Theodrada, then Abbess of the Monastery of the Humility of Our Lady of Argenteuil, on August 12, 800. The tunic, woven without doubt in the early centuries of our era in the Middle East, has survived through long centuries and troubled timess, and was hidden and cut up during the French Revolution. The sacred relic is enjoying a renewed popularity as an object of veneration.

Argenteuil's tunic during the 2016 ostention. / CC BY-SA 4.0/Simon de l'Ouest

Les raisons d'y croire :

- The history of the tunic is attested by reliable historical sources. Its existence has been documented since at least the 9th century.

- What remains of the tunic fits the description found in the Gospel according to John (Jn 19:23-24): woven from top to bottom in a single piece, seamless, and on a very rudimentary and ancient type of loom from the East, as the dyeing and weaving attest.

- It is stained with blood of type AB, the same blood type as in other Passion relics such as the Turin Shroud and the Oviedo Shroud.

- In 1892, a team of medical researchers identified blood on the Tunic, finding traces of blood globules, hematin crystals and iron. The bloodstains are nearly invisible to the naked eye, but their presence was confirmed by infra-red photographs made by Gerard Cordonnier in May, 1934. In 1893, two experts from the Gobelins laboratory attested to the great age of the fabric and the lack of seams.

- Pierre Barbet, in La Passion de Jésus-Christ selon le chirurgien (1997) , compares the ubication of the bloodstains of the two relics. As on the Shroud, the principle areas on the Tunic start from a large stain on the right shoulder and cascade obliquely over the boney projections.

- A 1998 study by French scientists André Marion & Gérard Lucotte performed a detailed comparison of the bloodstains on the Shroud of Turin and the back of the Tunic of Argenteuil: using computerized anthropometric models (allowing for simulation of the Tunic’s distortions while carrying the cross), as well as volunteers. To their surprise, their analysis showed that contrary to common opinion, it is more likely that the convict carried the whole cross, instead of merely horizontal beam. More importantly, Marion and his team found 9 corresponding points between bloodied areas on both the Shroud and the Tunic. They concluded that the “results seem to leave no doubts”, the correspondence is unlikely to be coincidental.

- Finally, devotion to this holy tunic has never waned: from the Carolingians to the Capetians, many kings and queens of France, as well as their ministers, have made pilgrimages to Argenteuil, or granted privileges to the monastery. Popes have also venerated this tunic.

Synthèse :

"When the soldiers had crucified Jesus, they took his clothes and divided them into four shares, a share for each soldier. They also took his tunic, but the tunic was seamless, woven in one piece from the top down. So they said to one another, 'Let’s not tear it, but cast lots for it to see whose it will be,' in order that the passage of scripture might be fulfilled [that says]: 'They divided my garments among them, and for my vesture they cast lots.' This is what the soldiers did." (Jn 19:23-24).

This is how Saint John, the evangelist who witnessed the crucifixion and then the resurrection, describes Christ's holy tunic. John is skipping unnecessary details, so since he evokes and describes this garment, we can assume that his intention is apologetic (this seamless tunic has always been seen as a symbol of the Church, evoking one of the last prayers of Christ to his heavenly Father: "That they may be one") and also serves to demonstrate the truth of his testimony.

Many scholars have taken the view that the tunic was carefully preserved by the first Christian communities, like the shroud (of Turin) and the sudarium (of Ovieto), as material relics left by the Son of God, whose body and spirit rose from the dead.

A pious tradition says that Pilate bought the tunic from the soldiers, then sold it to Christ's disciples. Peter, head of the Church, is said to have received it before leaving it with a Jewish tanner named Simon, in Jaffa (now Tel Aviv). The symbolism here is obvious: it was in Jaffa that Peter had his vision of the food, both pure and impure, that he was to eat (Acts 10:14). The Church, represented by the seamless tunic, took off universally from this place.

For the next few centuries, two traditions, which are not mutually exclusive, presented opposite stories. According to one, it was Saint Helena who "found" the tunic, around 327 or 328, along with the other famous relics of the Passion. The problem with this tradition is that Helena never mentioned the tunic. According to the other account, which we owe in particular to the Frankish chroniclers Gregory of Tours and Fredegar, the hiding place was not revealed by the descendants of the Jew Simon until 590. And it was some decades later, when the Sassanid emperor was threatening the region, that the piece of cloth was transferred to the Basilica of the Angels in Germia, a suburb of Constantinople.

Around 800, the reunification of the two parts of the old Roman Empire was being considered, and Charlemagne asked for the hand of Empress Irene: although the marriage never took place, gifts were exchanged, including the holy tunic, which entered the kingdom of the Franks. Emperor Charlemagne entrusted it to his daughter Theodrada, founder and abbess of the monastery of the Humility of Our Lady of Argenteuil, near Paris. According to the Benedictine monk Odo of Deuil, the precious tunic was brought to the monastery on August 12, 800. It has never left it since.

Over the many centuries, the holy tunic narrowly escaped destruction several times. Very soon after its arrival in Argenteuil, it somehow survived the destruction of the monastery itself by Viking raiders. Tradition has it that it had been hidden inside a wall. The monastery was not rebuilt until 150 years later, in 1003. It took another century and a half for the hiding place to be discovered, and the first authentic mention of the piece of clothing dates back to 1156, when Archbishop Hugh of Amiens organised an exhibition in the presence of King Louis VII. The tunic was then known in Latin as the cappa pueri Jesu, meaning "cloak of the Child Jesus": tradition says that it was woven by the Virgin Mary for her child, and that it miraculously grew with him during his earthly life.

The tunic survived many turbulent periods, including the many fires and destructions of the Hundred Years' War and the Wars of Religion. It was especially venerated by the pious King Louis XIII, his mother Marie of Medicis, his wife Anne of Austria, and his minister Richelieu.

During the French Revolution however, it was in the greatest danger. The convent was forced to close, and in June 1791 the relic was handed over to the Argenteuil parish church. Then on November 18, 1793, faced with the threat of confiscation of Church property under the Convention government, the parish priest, Fr. Ozet, cut it up into several pieces, hid them in various placed and entrusted some to trustworthy parishioners. He himself buried four pieces in his garden, before being sent to prison for two years. In 1795, Fr. Ozet had the tunic reconstructed with only 20 of the retrieved fragments, as some were lost irretrievably. These fragments were patched together on a piece of unbleached satin fabric.

The abbey was destroyed and the parish church became too small, so the famous French architect Théodore Ballu, who designed many public buildings in Paris, rebuilt the present-day church where the tunic was placed in a beautiful showcase reliquary to the right of the choir. Leo XIII declared the site a minor basilica in 1898. In the modern era, the tunic has been displayed every fifty years, with the exception of 2016, the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy.

In the 20th century, a solemn exposition took place in 1934, attracting large crowds. The first scientific studies were carried out, concluding that the fabric was ancient and of middle-eastern origin. In 1983, a year before the planned exhibition, the tunic was stolen under mysterious circumstances, then returned two months later under even more mysterious circumstances. On the scientific side, an Ecumenical and Scientific Committee for the Holy Tunic of Argenteuil (COSTA ) was set up in 1995. Current research does not prove that the tunic was worn by Jesus, but it does point to the probability: dating from the first centuries and stained with blood, it is made of very fine wool and is woven without seams, which corresponds perfectly to the Gospel description and the various episodes of the Passion: it is said to have been taken off Jesus for the scourging, then returned to him to carry the Cross, before he was stripped of it for good at the crucifixion.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the ancient Confraternity of the Holy Tunic was revived, and a solemn viewing was organised in 2016 by the current rector of the basilica, the Very Rev. Father Cariot. Given the unexpected success of the event (almost 200,000 people flocked to contemplate and venerate the tunic), he is planning to hold a new exposition in 2025, to celebrate the jubilee year and the 1,700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea.

Jacques de Guillebon, an essayist and journalist. He is a contributor to the French Catholic magazine La Nef.

Au-delà des raisons d'y croire :

Even if science is not able to determine its authencity, the Argenteuil tunic bears witness to the Passion and has been venerated by hundreds of thousands of faithful over the centuries. It is one of France's countless Christian treasures.

Aller plus loin :

Relics of the Christ by Joe Nickell, University Press of Kentucky (March 16, 2007)