- By theme

- Jesus

- The many proofs of Christ’s resurrection

- Saint Thomas Aquinas: God gave all the divine proofs we needed to believe

- The surpassing power of Christ's word

- Lewis’s trilemma: a proof of Jesus’s divinity

- God saves: the power of the holy name of Jesus

- Jesus spoke and acted as God's equal

- Jesus' divinity is actually implied in the Koran

- Jesus came at the perfect time of history

- Rabbinical sources testify to Jesus' miracles

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- An enduring prophecy and a series of miraculous events preventing the reconstruction of the Temple

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- Saint Peter, prince of the apostles

- Saint John the Apostle: an Evangelist and Theologian who deserves to be better known (d. 100)

- Saint Matthew, apostle, evangelist and martyr (d. 61)

- James the Just, “brother” of the Lord, apostle and martyr (d. 62 AD)

- Saint Matthias replaces Judas as an apostle (d. 63)

- The martyrs

- The protomartyr Saint Stephen (d. 31)

- Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, disciple of John and martyr (d. 155)

- Justin Martyr: philosopher and apologist (d.165)

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Agatha stops a volcano from destroying the city of Catania (d. 251)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Saint Boniface propagates Christianity in Germany (d. 754)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The martyrdom of Paul Miki and his companions (d. 1597)

- The martyrs of Angers and Avrillé (1794)

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- He braved torture to atone for his apostasy (d. 1818)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

- The Uganda martyrs: a recurring pattern in the persecution of Christians (1885)

- José Luis Sanchez del Rio, martyred at age 14 for Christ the King (d. 1928)

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- The Desert Fathers (3rd century)

- Saint Anthony of the Desert, a father of monasticism (d. 356)

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The surprising death of Father Emmanuel de Floris (d. 1992)

- The prophecies of Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (d. 1994)

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Augustine of Canterbury evangelises England (d. 604)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

- Saint Rainerius of Pisa: from musician to merchant to saint (d. 1160)

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Rose of Viterbo or How prayer can transform the world (d. 1252)

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence (d. 1317)

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

- Saint Peter Thomas (d. 1366): a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love (d. 1510)

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Saint Marie of the Incarnation, "the Teresa of New France" (d.1672)

- St. Francis di Girolamo's gift of reading hearts and souls (d. 1716)

- Rosa Venerini: moving in the ocean of the Will of God (d. 1728)

- Saint Jeanne-Antide Thouret: heroic perseverance and courage (d. 1826)

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833): the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

- Camille de Soyécourt, filled with divine fortitude (d. 1849)

- Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary (1858)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin" (d. 1862)

- Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble (1863)

- Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church (d. 1872)

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God” (d. 1919)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Lutgardis of Tongeren and the devotion to the Sacred Heart

- Saint Angela of Foligno (d. 1309) and "Lady Poverty"

- Saint John of the Cross: mystic, reformer, poet, and universal psychologist (+1591)

- Blessed Anne of Jesus: a Carmelite nun with mystical gifts (d.1621)

- Catherine Daniélou: a mystical bride of Christ in Brittany

- Saint Margaret Mary sees the "Heart that so loved mankind"

- Jesus makes Maria Droste zu Vischering the messenger of his Divine Heart (d. 1899)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée of Jesus' predictions concerning the Second World War (1922)

- Sister Josefa Menendez, apostle of divine mercy (d. 1923)

- Edith Royer (d. 1924) and the Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre

- Rozalia Celak, a mystic with a very special mission (d. 1944)

- Visionaries

- Saint Perpetua delivers her brother from Purgatory (203)

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Discovery of the Virgin Mary's house in Ephesus (1891)

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- Maria Valtorta's visions match data from the Israel Meteorological Service (1943)

- Berthe Petit's prophecies about the two world wars (d. 1943)

- Maria Valtorta saw only one pyramid at Giza in her visions... and she was right! (1944)

- The location of Saint Peter's village seen in a vision before its archaeological discovery (1945)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- Mariette Kerbage, the seer of Aleppo (1982)

- The 20,000 icons of Mariette Kerbage (2002)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Saint Augustine's conversion: "Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?" (386)

- Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534): a life in service of the truth

- Madame Acarie, "the servant of the servants of God" (d. 1618)

- Blaise Pascal (d.1662): Biblical prophecies are evidence

- Madame Élisabeth and the sweet smell of virtue (d. 1794)

- Jacinta, 10, offers her suffering to save souls from hell (d. 1920)

- Father Jean-Édouard Lamy: "another Curé of Ars" (d. 1931)

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- The Christian faith explains the diversity of religions

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Apparition of Our Lady of La Treille in northern France: prophecy and healings (600)

- Our Lady of Virtues saves the city of Rennes in Bretagne (1357)

- Mary stops the plague epidemic at Mount Berico (1426)

- Our Lady of Miracles heals a paralytic in Saronno (1460)

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- Savona: supernatural origin of the devotion to Our Lady of Mercy (1536)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- The “aldermen's vow”, or the Marian devotion of the people of Lyon (1643)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- Heaven confides in a shepherdess of Le Laus (1664-1718)

- Zeitoun, a two-year miracle (1968-1970)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- The five Marian apparitions that traced an "M" over France, and its new pilgrimage route

- A series of Marian apparitions and prophetic messages in Ukraine since the 19th century (1806)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- "Our Lady of the Poor" appears eight times in Banneux (1933)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Mary responds to the Vows of the Polish Nation (1956)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Seuca, Romania: apparitions and pleas of the Virgin Mary, "Queen of Light" (1995)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Mont Saint-Michel: Heaven watching over France

- The revelation of the hymn Axion Estin by the Archangel Gabriel (982)

- Angels give a supernatural belt to the chaste Thomas Aquinas (1243)

- The constant presence of demons and angels in the life of St Frances of Rome (d. 1440)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée escapes from prison with the help of an angel (1943)

- Saved by Angels: The Miracle on Highway 6 (2008)

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Peter Nolasco: a life dedicated to ransoming enslaved Christians (d. 1245)

- Rita of Cascia forgives her husband's murderer (1404)

- Saint Angela Merici: Christ came to serve, not to be served (d. 1540)

- Saint John of God: a life dedicated to the care of the poor, sick and those with mental disorders (d. 1550)

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Blessed Alix Le Clerc, encouraged by the Virgin Mary to found schools (d. 1622)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montreal's first teacher (d. 1700)

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Damian of Molokai: a leper for Christ (d. 1889)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Saint Dulce of the Poor, the Good Angel of Bahia (d. 1992)

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- The miracle of liquefaction of the blood of St. Januarius (d. 431)

- The miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua (d. 1231)

- Saint Pius V and the miracle of the Crucifix (1565)

- Saint Philip Neri calls a teenager back to life (1583)

- The resurrection of Jérôme Genin (1623)

- Saint Francis de Sales brings back to life a victim of drowning (1623)

- Saint John Bosco and the promise kept beyond the grave (1839)

- The day the sun danced at Fatima (1917)

- Pius XII and the miracle of the sun at the Vatican (1950)

- When Blessed Charles de Foucauld saved a young carpenter named Charle (2016)

- Reinhard Bonnke: 89 million conversions (d. 2019)

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Our Lady at Pellevoisin: "I am all merciful" (1876)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- The miraculous healing of Marie Bailly and the conversion of Dr. Alexis Carrel (1902)

- Gemma Galgani: healed to atone for sinners' faults (d. 1903)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The extraordinary healing of Alice Benlian in the Church of the Holy Cross in Damascus (1983)

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Healed by St Charbel Makhlouf, her scars bleed each month for the benefit of unbelievers (1993)

- The miracle that led to Brother André's canonisation (1999)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- He had “zero” chance of living: a baby's miraculous recovery (2015)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Dying in the odour of sanctity

- The body of Saint Cecilia found incorrupt (d. 230)

- Saint Claudius of Besançon: a quiet leader, a calm presence, and a strong belief in the value of prayer (d. 699)

- Stanislaus Kostka's burning love for God (d. 1568)

- Saint Germaine of Pibrac: God's little Cinderella (d. 1601)

- Blessed Antonio Franco, bishop and defender of the poor (d. 1626)

- Giuseppina Faro, servant of God and of the poor (d. 1871)

- The incorrupt body of Marie-Louise Nerbollier, the visionary from Diémoz (d. 1910)

- The great exhumation of Saint Charbel (1950)

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Saidnaya icon exudes a wonderful fragrance (1988)

- Our Lady weeps in a bishop's hands (1995)

- Stigmates

- The venerable Lukarda of Oberweimar shares her spiritual riches with her convent (d. 1309)

- Florida Cevoli: a heart engraved with the cross (d. 1767)

- Blessed Maria Grazia Tarallo, mystic and stigmatist (d. 1912)

- Saint Padre Pio: crucified by Love (1918)

- Elena Aiello: "a Eucharistic soul"

- A Holy Triduum with a Syrian mystic, witnessing the sufferings of Christ (1987)

- A Holy Thursday in Soufanieh (2004)

- Eucharistic miracles

- Lanciano: the first and possibly the greatest Eucharistic miracle (750)

- A host came to her: 11-year-old Imelda received Communion and died in ecstasy (1333)

- Faverney's hosts miraculously saved from fire

- A tsunami recedes before the Blessed Sacrament (1906)

- Buenos Aires miraculous host sent to forensic lab, found to be heart muscle (1996)

- Relics

- The Veil of Veronica, known as the Manoppello Image

- For centuries, the Shroud of Turin was the only negative image in the world

- The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

- Saint Louis (d. 1270) and the relics of the Passion

- The miraculous rescue of the Shroud of Turin (1997)

- A comparative study of the blood present in Christ's relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Francis Xavier Samson Libermann, Jewish convert to Catholicism (1824)

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal and the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne (1842)

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Olivier's conversion story: from Pesach to the Christian Easter (2000)

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- He met Jesus while looking for Muhammad (1990)

- Selma's journey to baptism (1996)

- Soumia, converted to Jesus as she hears Christmas carols (2003)

- How Aïsha, a Muslim convert, found Jesus (2004)

- Amir chooses Christ, at the risk of becoming homeless (2004)

- Souad Brahimi: brought to Jesus by Mary (2012)

- Pursued by God: Khadija's story (2023)

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- The conversion of an executioner during the Terror (1830)

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- From agnostic to Catholic Trappist monk (1909)

- Dazzled by God: Madeleine Delbrêl's story (1924)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Nelly Gillant: from Reiki Master to Disciple of Christ (2018)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Jesus audibly calls Alphonsus Liguori to follow him (1723)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Jesus' message to Myrna Nazzour (1984)

- Alicja Lenczewska: conversations with Jesus (1985)

- Vassula Ryden and the "True Life in God" (1985)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Invited to the celestial court: the story of Chantal (2017)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Ambrose of Milan finds the bodies of the martyrs Gervasius and Protasius (386)

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- Seven golden stars reveal the future location of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery (1132)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Saint Zita and the miracle of the cloak (13th c.)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- A celestial music comforts Elisabetta Picenardi on her deathbed (d. 1468)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- The strange adventure of Yves Nicolazic (1623)

- Julien Maunoir miraculously learns Breton (1626)

- Pierre de Keriolet: with Mary, one cannot be lost (1636)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- A hundred years before it happened, Saint Andrew Bobola predicted that Poland would be back on the map (1819)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Don Bosco's angel dog: Grigio (1854)

- The purifying flames of Sophie-Thérèse de Soubiran La Louvière (1861)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- Lost for over a century, a Russian icon reappears (1930)

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- He should have died of hypothermia in Soviet jails (1972)

- God protects a secret agent (1975)

- Flowing lava stops at church doors (1977)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- The miracles of Saint Juliana of Nicomedia (1994)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- The providential finding of the Mary of Nazareth International Center's future site (2000)

- Syrian Monastery shielded from danger multiple times (2011-2020)

- Jesus

- Who are we?

- Make a donation

TOUTES LES RAISONS DE CROIRE

Les moines

n°126

Puglia (Italy)

1887 - 1968

Saint Pio of Pietrelcina: How God works wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

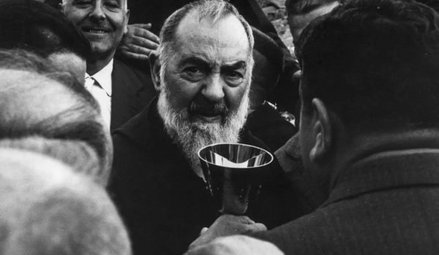

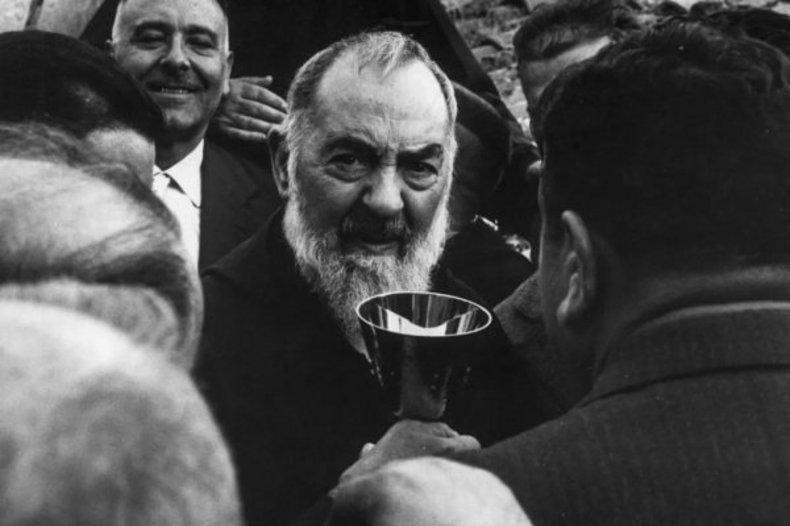

Padre Pio, in his own words "a poor brother who prays", is among the greatest saints. He was favored with mystical graces from childhood, but was also often violently attacked by the devil, a struggle that lasted throughout his life. He joined the Capuchins in 1903 and was ordained in 1910. His life, punctuated by inexplicable phenomena that were investigated and recognised as authentic, was marked by great charity. The hospital he managed to build before his death on September 23, 1968, despite a host of obstacles, is proof of it. The ceremony of Padre Pio's canonisationin 2002 by John Paul II brought together 150,000 faithful in St Peter's Square in Rome.

Padre Pio among the faithful / © CC0/wikimedia

Les raisons d'y croire :

- The Passion wounds received by Padre Pio, initially the subject of controversy, were rigorously analysed and authenticated as supernatural, notably by Doctor Festa on October 10, 1919: they were not the fruit of the monk's imagination, and were not caused by self-mutilation. The doctor emphasised that the wounds never changed over time, and that they did not fester or become infected, as a natural wound would.

An incredible feature of these stigmata is that they mysteriously disappeared just moments before the celebration of Padre Pio's last Mass, on September 22, 1968. One of the doctors called to Padre Pio's bedside that day declared that it was "an occurrence outside any type of clinical behaviour, and of an extra-natural nature".

- To this day, there is no scientific explanation for the recurring diabolical attacks meant to hurt or intimidate him (objects moving by themselves, bed overturned, unusual noises, blows to the face and body, etc.).

- Padre Pio's bilocations, all of which had a spiritual purpose, have been attested beyond doubt. Numerous testimonies demonstrate his presence in two places at the same time: he intervened miles away from his monastery while remaining in his cell praying. For example, he prevented the suicide of an Italian officer during the war.

- The cures recorded during his lifetime and after his death through his intercession - often from incurable illnesses diagnosed by doctors in great detail - are fully attested. For his canonisation, 73 testimonies of healings obtained through his prayers were collected, and recorded in 104 volumes.

- Many of his prophecies came true, such as the one in 1947 when he told a young Polish student named Karol Wojtyla that he would one day be Pope.

- In 1963 alone, more than 100,000 people signed up to go to confession to him. Padre Pio used his gift of reading souls to help penitents: many of them testified to the radical change they experienced in confession with Padre Pio, who read their souls.

- Padre Pio's monastery received an enormous number of gifts. None of them went to him personally, but all were used to build a hospital that currently treats almost 60,000 people every year. It is clear that Padre Pio was not acting out of self-interest.

- Exposed to the veneration of the faithful in the crypt of San Giovanni Rotondo (Puglia, Italy), the body of Saint Padre Pio has remained incorrupt for 55 years.

- During his life and for half a century, huge crowds visited the saint, without anyone - clergy, doctors, theologians, political authorities or scientists - ever detecting any duplicity or deception on Padre Pio's part. But the monk's popularity was problematic and he was subjected to a great deal of scrutiny.

- The observed phenomena (stigmata, extraordinary perfumes, visions, locutions, the gift of clairvoyance, bilocations, etc.) were never senseless prodigies: all of them, without exception, were signs and instruments at the service of the Gospel, in perfect coherence with the teaching of the Church.

- Padre Pio's view of the experiences he had was entirely consistent with that of the Church. In his eyes, they remained secondary, marginal and subordinate to what is essential: the love of Christ.

- Despite the disciplinary measures imposed on him from 1922 to 1964, the future saint remained totally obedient to his direct superiors and to the ecclesiastical hierarchy as a whole.

Synthèse :

Francisco Forgione was born in 1887 in Pietrelcina, an Italian village near Benevento in Campania, south of Rome. The fourth child of Grazio Forgione and Maria Giuseppa Di Nunzio, modest farm workers, he grew up outside, but his health was fragile: the child was prone to disturbed sleep and bouts of fever made him unusually tired. He loved solitude, nature and contemplation. His father thought he was not cut out to be a farmer, given his physical frailty. This realisation was providential: he dreamt of becoming a religious and join the Capuchins.

After his father left for America, his mother entrusted him to the care of a priest uncle, Don Pannullo. This priest obtained his admission to the Capuchins in Morcone (Italy). On January 22, 1903, after saying goodbye to his family, the young man entered the monastery. From this time onwards, Br. Pio received mystical graces. He had three visions before he even embraced religious life. The first bilocations occurred. These phenomena never prevented him from fulfilling his religious duties and participating in community life. On the contrary, he was an excellent religious, and his brothers had great esteem for him and served him as he served them in faith and detachment.

Daily life was hard: discomfort, lack of conveniences, the rare journeys made by donkey or cart; food was frugal and sleep was interrupted every night by the liturgy of the hours. Strangely enough, his poor health resisted this kind of life. He just wanted to live live the kind of life Jesus of Nazareth had.

After passing his exams, he took his final vows on January 27, 1907. This was the beginning of a strange period for him, full of extraordinary phenomena, but also of suffering and contradictions. First of all, he suffered from a variety of ailments. A bronchoalveolitis in his left lung forced him to leave the monastery temporarily (but for almost a whole year) to receive appropriate treatment. Then the doctors authorised him to return to the cloister. He was soon ordained a sub-deacon. But he suffered a relapse six months later, forcing him to return to his family for several months. One of his teachers, Father Bernardino, said of him that he stood out not by his intelligence but by his humility, gentleness and obedience.

Then, the devil's attacks became stronger. They were of two kinds: internal (temptations to abandon the contemplative life, to hate the clergy, etc.), and external: objects moving by themselves, an inkwell thrown against a wall of his cell, an overturned bed, unusual noises whose source was indefinable, blows to the face and body, causing bruising and haemorrhaging, etc. These manifestations are surprising, of course, but they are fairly common among the saints.

Some of the facts are chilling: several of the saint's letters to his superiors were found blank, full of erasures or ink stains. One day he received a visit from his spiritual director, Father Agostino da San Marco in Lamis, in his room in Pietrelcina. The visit surprised the young Capuchin, as the priest was not in the habit of coming to him unannounced. Immediately, the visitor tried to persuade him to give up the religious life, on the pretext that his austerities exceeded his natural capacities; finally, he explained to him that his extraordinary phenomena were the fruit of his unbridled psychology... Surprised, Brother Pio asked Christ to enlighten him. A moment later, he suggested that his visitor pray to the Holy Name of Jesus: "Long live Jesus!" At these words, the "visiting priest" literally disappeared in an instant.

On August 10, 1910, he was ordained a priest in Benevento Cathedral. After a few hours spent with his family, the devil, whom he nicknamed "Bluebeard", or the "Mustachian", attacked again. This time, the young Capuchin was the victim of various temptations and obsessions, day and night. His correspondence at the time mentions external manifestations identical to those experienced by great saints over the centuries, from Saint Anthony of Egypt (d. 356) to the holy Curé of Ars (d. 1859).

At the same time, he became closer to God every day, through prayer, asceticism and self-abasement. Although he had never received any in-depth teaching on the subject, his capacity for discernment left him speechless: "These heavenly favours produced in me [...] these three results: a knowledge of God, of his incredible greatness; a great knowledge of myself and a profound feeling of humility."

Some people thought Padre Pio's stigmata were a figment of his imagination or an act of self-mutilation. In either case, this is baseless. On the one hand, his psychology shows no signs of morbidity or pain. He was a perfectly balanced man, as attested by the many medical reports drawn up from 1919 onwards. On October 10, 1919, Doctor Festa examined Brother Pio and concluded that the stigmata had a non-natural origin. He visited Brother Pio until 1925, stating that the wounds had never changed over time and, what's more, did not fester or become infected like any natural wound. On the other hand, the clinical evolution of the wounds, far from being unpredictable, followed a particular pattern: they only opened on September 20, 1918, the date on which he joined the monastery of San Giovanni Rotondo, having been declared unfit for military service for health reasons; and they did not disappear until September 22, 1968, during the celebration of his last mass - something that the religious realised shortly afterwards. One of the doctors called to his bedside that day declared that it was "something outside of all types of clinical behaviour, and of an extra-natural nature".

After Padre Pio arrived at the monastery of San Giovanni Rotondo, things began to slowly change: although the saint hid the wounds on his hands with mittens, the news of his stigmatisation spread fast around the region, and soon hundreds of the faithful were flocking to the place to see, hear and touch the holy monk.

As usually happens when God makes himself present in a powerful way, the devil redoubled his attacks - thousands of saints' lives bear witness to this. A rumour arose calling into question Padre Pio's good faith and morality. Local officials were upset by the disturbance caused by the spontaneous pilgrimage around the convent. The local and then the national press got involved. Reluctantly, the saint became a celebrity. A postal sorting service was set up in the community, as so many letters reached the convent. Here and there, people began trying to steal an object, a piece of clothing belonging to him, even beard hairs... Later, a slanderous rumour spread and reached the Holy Office alleging that the Capuchins were fighting to get their hands on the donations collected by the saint! On October 14, 1920, violent clashes in San Giovanni Rotondo between socialists and fascists left 14 people dead. Some blamed Padre Pio, "the obscurantist monk", without reason.

In a bid to put a stop to these "disturbances", the police, aided by some of the clergy, took radical measures: the saint would have to say mass in a private place and would no longer be able to hear confessions. This was the beginning of a long and terrible isolation that Padre Pio endured with superhuman serenity: no one ever heard him say a negative word about anyone. In any case, it was too late: the "vox populi" had recognised the sanctity of the humble monk. On June 25, 1923, despite the bans in force, 5,000 people demonstrated outside the monastery to demand that the sanctions be lifted. Little by little, the situation was providentially reversed: the saint's main detractors were in turn accused of lies and false testimony. In the spring of 1934, Padre Pio regained the right to hear confessions.

Another affair soon cast a shadow over the saint's life. Hundreds of thousands of faithful sent donations to the monastery. Of course, because of his vow of poverty, the saint did not have access to this money. But some accused him of enriching himself through popular credulity. In reality, these funds were set aside for the construction of a hospital equipped with cutting-edge technology, envisioned by Padre Pio. The major works were completed in December 1949. The building was inaugurated on May 5, 1956. It is a state of the art medical complex, with all specialities represented.

Brother Pio was 70 years old. His popularity and reputation could have led people to believe that his life would be peaceful from then on. On the contrary, serious but unfounded accusations once again reached the Roman Curia. Padre Pio once again had to retire from public life. The man suffered, but the Christian entrusted himself body and soul to providence. He showed perfect obedience.

In the summer of 1959, his mail was systematically opened. Microphones were installed in the places where he confessed. The surveillance lasted four months. Women confessing to him were never allowed to stay with him after the sacrament, and men were only allowed in the monastery church. In April 1961, it was stipulated that his Mass must not exceed 40 minutes, otherwise it would be timed!

The saint prayed even more earnestly, confiding in God and in the Virgin Mary, who appeared to him. On August 10, 1960, he celebrated the jubilee of his ordination. In such circumstances, he expected to celebrate in solitude. That day, 20,000 people flocked to San Giovanni Rotondo and 70 Italian bishops sent him a message of congratulations, including a certain Mgr Montini, the future Saint Paul VI. From December 1962 (the first session of the Second Vatican Council), dozens of bishops staying in Rome visited him. God was faithful: on January 30 ,1964, Cardinal Ottaviani informed the Capuchins that Pope Paul VI intended to restore full freedom to the humble Capuchin. In 1967 alone, 25,000 people went to confession to him.

The last two years of his life were physically exhausting but he did not abandon any of his duties. He celebrated his daily mass, which was attended right up to the end by a great number of faithful. His death on September 23, 1968, caused a wave of emotion in Italy and beyond. Countless people travelled to San Giovanni Rotondo to pay their last respects to the humble Capuchin.

Beatified on May 2, 1999, Saint John Paul II canonized him on June 16, 2002.

Patrick Sbalchiero

Au-delà des raisons d'y croire :

Padre Pio's fortitude and patience amisdt trials, his unwavering attachment to Christ, his common sense and his charity beyond measure make him an extraordinary man, but above all he is an example of what God's grace can operate in a heart fully opened and given to God.

Aller plus loin :

Padre Pio: The True Story by C. Bernard Ruffin, Our Sunday Visitor; 3rd ed. edition (September 21, 2018)