- By theme

- Jesus

- The many proofs of Christ’s resurrection

- Saint Thomas Aquinas: God gave all the divine proofs we needed to believe

- The surpassing power of Christ's word

- Lewis’s trilemma: a proof of Jesus’s divinity

- God saves: the power of the holy name of Jesus

- Jesus spoke and acted as God's equal

- Jesus' divinity is actually implied in the Koran

- Jesus came at the perfect time of history

- Rabbinical sources testify to Jesus' miracles

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- An enduring prophecy and a series of miraculous events preventing the reconstruction of the Temple

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- Saint Peter, prince of the apostles

- Saint John the Apostle: an Evangelist and Theologian who deserves to be better known (d. 100)

- Saint Matthew, apostle, evangelist and martyr (d. 61)

- James the Just, “brother” of the Lord, apostle and martyr (d. 62 AD)

- Saint Matthias replaces Judas as an apostle (d. 63)

- The martyrs

- The protomartyr Saint Stephen (d. 31)

- Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, disciple of John and martyr (d. 155)

- Justin Martyr: philosopher and apologist (d.165)

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Agatha stops a volcano from destroying the city of Catania (d. 251)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Saint Boniface propagates Christianity in Germany (d. 754)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The martyrdom of Paul Miki and his companions (d. 1597)

- The martyrs of Angers and Avrillé (1794)

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- He braved torture to atone for his apostasy (d. 1818)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

- The Uganda martyrs: a recurring pattern in the persecution of Christians (1885)

- José Luis Sanchez del Rio, martyred at age 14 for Christ the King (d. 1928)

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- The Desert Fathers (3rd century)

- Saint Anthony of the Desert, a father of monasticism (d. 356)

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The surprising death of Father Emmanuel de Floris (d. 1992)

- The prophecies of Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (d. 1994)

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Augustine of Canterbury evangelises England (d. 604)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

- Saint Rainerius of Pisa: from musician to merchant to saint (d. 1160)

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

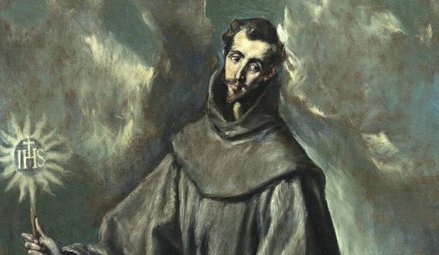

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Rose of Viterbo or How prayer can transform the world (d. 1252)

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence (d. 1317)

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

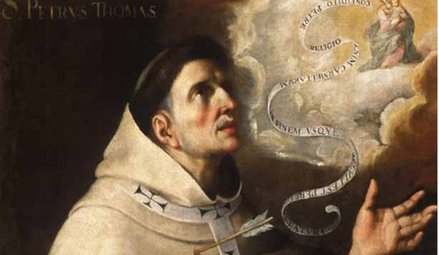

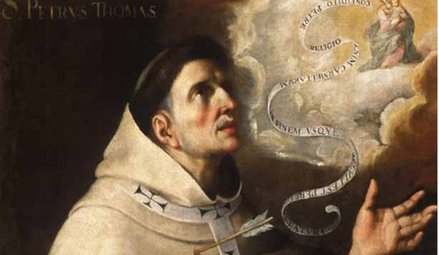

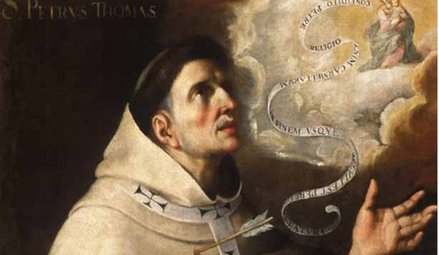

- Saint Peter Thomas (d. 1366): a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love (d. 1510)

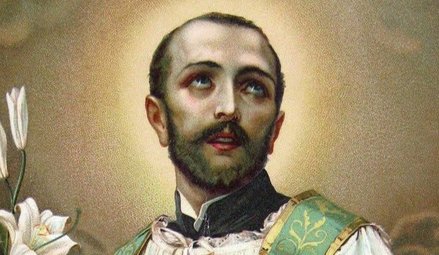

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Saint Marie of the Incarnation, "the Teresa of New France" (d.1672)

- St. Francis di Girolamo's gift of reading hearts and souls (d. 1716)

- Rosa Venerini: moving in the ocean of the Will of God (d. 1728)

- Saint Jeanne-Antide Thouret: heroic perseverance and courage (d. 1826)

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833): the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

- Camille de Soyécourt, filled with divine fortitude (d. 1849)

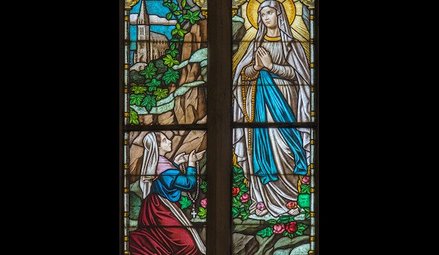

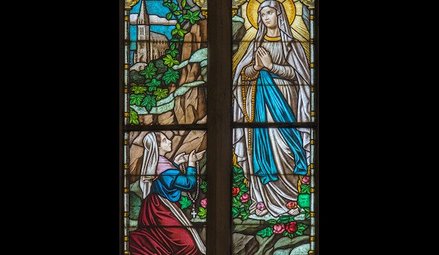

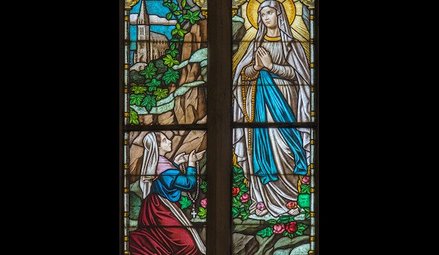

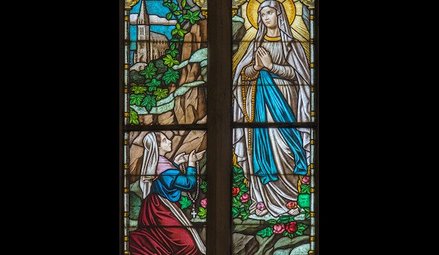

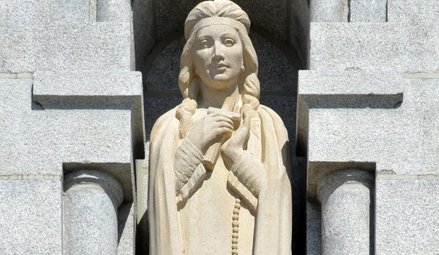

- Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary (1858)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin" (d. 1862)

- Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble (1863)

- Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church (d. 1872)

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God” (d. 1919)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Lutgardis of Tongeren and the devotion to the Sacred Heart

- Saint Angela of Foligno (d. 1309) and "Lady Poverty"

- Saint John of the Cross: mystic, reformer, poet, and universal psychologist (+1591)

- Blessed Anne of Jesus: a Carmelite nun with mystical gifts (d.1621)

- Catherine Daniélou: a mystical bride of Christ in Brittany

- Saint Margaret Mary sees the "Heart that so loved mankind"

- Jesus makes Maria Droste zu Vischering the messenger of his Divine Heart (d. 1899)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée of Jesus' predictions concerning the Second World War (1922)

- Sister Josefa Menendez, apostle of divine mercy (d. 1923)

- Edith Royer (d. 1924) and the Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre

- Rozalia Celak, a mystic with a very special mission (d. 1944)

- Visionaries

- Saint Perpetua delivers her brother from Purgatory (203)

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Discovery of the Virgin Mary's house in Ephesus (1891)

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- Maria Valtorta's visions match data from the Israel Meteorological Service (1943)

- Berthe Petit's prophecies about the two world wars (d. 1943)

- Maria Valtorta saw only one pyramid at Giza in her visions... and she was right! (1944)

- The location of Saint Peter's village seen in a vision before its archaeological discovery (1945)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- Mariette Kerbage, the seer of Aleppo (1982)

- The 20,000 icons of Mariette Kerbage (2002)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Saint Augustine's conversion: "Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?" (386)

- Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534): a life in service of the truth

- Madame Acarie, "the servant of the servants of God" (d. 1618)

- Blaise Pascal (d.1662): Biblical prophecies are evidence

- Madame Élisabeth and the sweet smell of virtue (d. 1794)

- Jacinta, 10, offers her suffering to save souls from hell (d. 1920)

- Father Jean-Édouard Lamy: "another Curé of Ars" (d. 1931)

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- The Christian faith explains the diversity of religions

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Apparition of Our Lady of La Treille in northern France: prophecy and healings (600)

- Our Lady of Virtues saves the city of Rennes in Bretagne (1357)

- Mary stops the plague epidemic at Mount Berico (1426)

- Our Lady of Miracles heals a paralytic in Saronno (1460)

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- Savona: supernatural origin of the devotion to Our Lady of Mercy (1536)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- The “aldermen's vow”, or the Marian devotion of the people of Lyon (1643)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- Heaven confides in a shepherdess of Le Laus (1664-1718)

- Zeitoun, a two-year miracle (1968-1970)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- The five Marian apparitions that traced an "M" over France, and its new pilgrimage route

- A series of Marian apparitions and prophetic messages in Ukraine since the 19th century (1806)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- "Our Lady of the Poor" appears eight times in Banneux (1933)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Mary responds to the Vows of the Polish Nation (1956)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Seuca, Romania: apparitions and pleas of the Virgin Mary, "Queen of Light" (1995)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Mont Saint-Michel: Heaven watching over France

- The revelation of the hymn Axion Estin by the Archangel Gabriel (982)

- Angels give a supernatural belt to the chaste Thomas Aquinas (1243)

- The constant presence of demons and angels in the life of St Frances of Rome (d. 1440)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée escapes from prison with the help of an angel (1943)

- Saved by Angels: The Miracle on Highway 6 (2008)

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Peter Nolasco: a life dedicated to ransoming enslaved Christians (d. 1245)

- Rita of Cascia forgives her husband's murderer (1404)

- Saint Angela Merici: Christ came to serve, not to be served (d. 1540)

- Saint John of God: a life dedicated to the care of the poor, sick and those with mental disorders (d. 1550)

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Blessed Alix Le Clerc, encouraged by the Virgin Mary to found schools (d. 1622)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montreal's first teacher (d. 1700)

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Damian of Molokai: a leper for Christ (d. 1889)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Saint Dulce of the Poor, the Good Angel of Bahia (d. 1992)

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- The miracle of liquefaction of the blood of St. Januarius (d. 431)

- The miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua (d. 1231)

- Saint Pius V and the miracle of the Crucifix (1565)

- Saint Philip Neri calls a teenager back to life (1583)

- The resurrection of Jérôme Genin (1623)

- Saint Francis de Sales brings back to life a victim of drowning (1623)

- Saint John Bosco and the promise kept beyond the grave (1839)

- The day the sun danced at Fatima (1917)

- Pius XII and the miracle of the sun at the Vatican (1950)

- When Blessed Charles de Foucauld saved a young carpenter named Charle (2016)

- Reinhard Bonnke: 89 million conversions (d. 2019)

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Our Lady at Pellevoisin: "I am all merciful" (1876)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- The miraculous healing of Marie Bailly and the conversion of Dr. Alexis Carrel (1902)

- Gemma Galgani: healed to atone for sinners' faults (d. 1903)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The extraordinary healing of Alice Benlian in the Church of the Holy Cross in Damascus (1983)

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Healed by St Charbel Makhlouf, her scars bleed each month for the benefit of unbelievers (1993)

- The miracle that led to Brother André's canonisation (1999)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- He had “zero” chance of living: a baby's miraculous recovery (2015)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Dying in the odour of sanctity

- The body of Saint Cecilia found incorrupt (d. 230)

- Saint Claudius of Besançon: a quiet leader, a calm presence, and a strong belief in the value of prayer (d. 699)

- Stanislaus Kostka's burning love for God (d. 1568)

- Saint Germaine of Pibrac: God's little Cinderella (d. 1601)

- Blessed Antonio Franco, bishop and defender of the poor (d. 1626)

- Giuseppina Faro, servant of God and of the poor (d. 1871)

- The incorrupt body of Marie-Louise Nerbollier, the visionary from Diémoz (d. 1910)

- The great exhumation of Saint Charbel (1950)

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Saidnaya icon exudes a wonderful fragrance (1988)

- Our Lady weeps in a bishop's hands (1995)

- Stigmates

- The venerable Lukarda of Oberweimar shares her spiritual riches with her convent (d. 1309)

- Florida Cevoli: a heart engraved with the cross (d. 1767)

- Blessed Maria Grazia Tarallo, mystic and stigmatist (d. 1912)

- Saint Padre Pio: crucified by Love (1918)

- Elena Aiello: "a Eucharistic soul"

- A Holy Triduum with a Syrian mystic, witnessing the sufferings of Christ (1987)

- A Holy Thursday in Soufanieh (2004)

- Eucharistic miracles

- Lanciano: the first and possibly the greatest Eucharistic miracle (750)

- A host came to her: 11-year-old Imelda received Communion and died in ecstasy (1333)

- Faverney's hosts miraculously saved from fire

- A tsunami recedes before the Blessed Sacrament (1906)

- Buenos Aires miraculous host sent to forensic lab, found to be heart muscle (1996)

- Relics

- The Veil of Veronica, known as the Manoppello Image

- For centuries, the Shroud of Turin was the only negative image in the world

- The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

- Saint Louis (d. 1270) and the relics of the Passion

- The miraculous rescue of the Shroud of Turin (1997)

- A comparative study of the blood present in Christ's relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Francis Xavier Samson Libermann, Jewish convert to Catholicism (1824)

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal and the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne (1842)

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Olivier's conversion story: from Pesach to the Christian Easter (2000)

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- He met Jesus while looking for Muhammad (1990)

- Selma's journey to baptism (1996)

- Soumia, converted to Jesus as she hears Christmas carols (2003)

- How Aïsha, a Muslim convert, found Jesus (2004)

- Amir chooses Christ, at the risk of becoming homeless (2004)

- Souad Brahimi: brought to Jesus by Mary (2012)

- Pursued by God: Khadija's story (2023)

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- The conversion of an executioner during the Terror (1830)

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- From agnostic to Catholic Trappist monk (1909)

- Dazzled by God: Madeleine Delbrêl's story (1924)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Nelly Gillant: from Reiki Master to Disciple of Christ (2018)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Jesus audibly calls Alphonsus Liguori to follow him (1723)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Jesus' message to Myrna Nazzour (1984)

- Alicja Lenczewska: conversations with Jesus (1985)

- Vassula Ryden and the "True Life in God" (1985)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Invited to the celestial court: the story of Chantal (2017)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Ambrose of Milan finds the bodies of the martyrs Gervasius and Protasius (386)

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- Seven golden stars reveal the future location of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery (1132)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Saint Zita and the miracle of the cloak (13th c.)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- A celestial music comforts Elisabetta Picenardi on her deathbed (d. 1468)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- The strange adventure of Yves Nicolazic (1623)

- Julien Maunoir miraculously learns Breton (1626)

- Pierre de Keriolet: with Mary, one cannot be lost (1636)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- A hundred years before it happened, Saint Andrew Bobola predicted that Poland would be back on the map (1819)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Don Bosco's angel dog: Grigio (1854)

- The purifying flames of Sophie-Thérèse de Soubiran La Louvière (1861)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- Lost for over a century, a Russian icon reappears (1930)

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- He should have died of hypothermia in Soviet jails (1972)

- God protects a secret agent (1975)

- Flowing lava stops at church doors (1977)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- The miracles of Saint Juliana of Nicomedia (1994)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- The providential finding of the Mary of Nazareth International Center's future site (2000)

- Syrian Monastery shielded from danger multiple times (2011-2020)

- Jesus

- Who are we?

- Make a donation

< Toutes les raisons sont ici !

TOUTES LES RAISONS DE CROIRE

- Jesus

- The many proofs of Christ’s resurrection

- Saint Thomas Aquinas: God gave all the divine proofs we needed to believe

- The surpassing power of Christ's word

- Lewis’s trilemma: a proof of Jesus’s divinity

- God saves: the power of the holy name of Jesus

- Jesus spoke and acted as God's equal

- Jesus' divinity is actually implied in the Koran

- Jesus came at the perfect time of history

- Rabbinical sources testify to Jesus' miracles

- Mary

- The Church

- The Bible

- An enduring prophecy and a series of miraculous events preventing the reconstruction of the Temple

- The authors of the Gospels were either eyewitnesses or close contacts of those eyewitnesses

- Onomastics support the historical reliability of the Gospels

- The New Testament was not altered

- The New Testament is the best-attested manuscript of Antiquity

- The Gospels were written too early after the facts to be legends

- Archaeological finds confirm the reliability of the New Testament

- The criterion of embarrassment proves that the Gospels tell the truth

- The dissimilarity criterion strengthens the case for the historical reliability of the Gospels

- 84 details in Acts verified by historical and archaeological sources

- The unique prophecies that announced the Messiah

- The time of the coming of the Messiah was accurately prophesied

- The prophet Isaiah's ultra accurate description of the Messiah's sufferings

- Daniel's "Son of Man" is a portrait of Christ

- The Apostles

- Saint Peter, prince of the apostles

- Saint John the Apostle: an Evangelist and Theologian who deserves to be better known (d. 100)

- Saint Matthew, apostle, evangelist and martyr (d. 61)

- James the Just, “brother” of the Lord, apostle and martyr (d. 62 AD)

- Saint Matthias replaces Judas as an apostle (d. 63)

- The martyrs

- The protomartyr Saint Stephen (d. 31)

- Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, disciple of John and martyr (d. 155)

- Justin Martyr: philosopher and apologist (d.165)

- Saint Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon: the fortitude of faith (177 AD)

- Saint Agatha stops a volcano from destroying the city of Catania (d. 251)

- Saint Lucy of Syracuse, virgin and martyr for Christ (d. 304)

- Saint Boniface propagates Christianity in Germany (d. 754)

- Thomas More: “The king’s good servant, but God’s first”

- The martyrdom of Paul Miki and his companions (d. 1597)

- The martyrs of Angers and Avrillé (1794)

- The Martyrs of Compiègne (1794)

- The Vietnamese martyrs Father Andrew Dung-Lac and his 116 companions (17th-19th centuries)

- He braved torture to atone for his apostasy (d. 1818)

- Blaise Marmoiton: the epic journey of a missionary to New Caledonia (d. 1847)

- The Uganda martyrs: a recurring pattern in the persecution of Christians (1885)

- José Luis Sanchez del Rio, martyred at age 14 for Christ the King (d. 1928)

- Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Knight of the Immaculate (d. 1941)

- The monks

- The Desert Fathers (3rd century)

- Saint Anthony of the Desert, a father of monasticism (d. 356)

- Saint Benedict, father of Western monasticism (d. 550)

- Saint Bruno the Carthusian (d.1101): the miracle of a hidden life

- Blessed Angelo Agostini Mazzinghi: the Carmelite with flowers pouring from his mouth (d. 1438)

- Monk Abel of Valaam's accurate prophecies about Russia (d. 1841)

- The more than 33,000 miracles of Saint Charbel Maklouf (d. 1898)

- Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (d. 1968): How God worked wonders through "a poor brother who prays"

- The surprising death of Father Emmanuel de Floris (d. 1992)

- The prophecies of Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (d. 1994)

- The saints

- Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary (19 BC)

- Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr (d. 68 or 70)

- Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel (d. 117)

- Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker (d. 270)

- Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism (d. 397)

- Saint Augustine of Canterbury evangelises England (d. 604)

- Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns (d. 623)

- Saint Rainerius of Pisa: from musician to merchant to saint (d. 1160)

- Saint Dominic of Guzman (d.1221): an athlete of the faith

- Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi (d. 1226)

- Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

- Saint Rose of Viterbo or How prayer can transform the world (d. 1252)

- Saint Simon Stock receives the scapular of Mount Carmel from the hands of the Virgin Mary

- The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

- Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence (d. 1317)

- The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

- Saint Peter Thomas (d. 1366): a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

- Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

- Saint Catherine of Genoa and the Fire of God's love (d. 1510)

- Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls (d. 1539)

- Saint Ignatius of Loyola (d. 1556): "For the greater glory of God"

- Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy porter" (d. 1617)

- Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification (d. 1639)

- Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome (d.1651)

- Saint Marie of the Incarnation, "the Teresa of New France" (d.1672)

- St. Francis di Girolamo's gift of reading hearts and souls (d. 1716)

- Rosa Venerini: moving in the ocean of the Will of God (d. 1728)

- Saint Jeanne-Antide Thouret: heroic perseverance and courage (d. 1826)

- Seraphim of Sarov (1759-1833): the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

- Camille de Soyécourt, filled with divine fortitude (d. 1849)

- Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary (1858)

- Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

- Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin" (d. 1862)

- Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble (1863)

- Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church (d. 1872)

- Saints Louis and Zelie Martin, the parents of Saint Therese of Lisieux (d. 1894 and 1877)

- The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God” (d. 1919)

- Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy (d. 1938)

- Brother Marcel Van (d.19659): a "star has risen in the East"

- Doctors

- The mystics

- Lutgardis of Tongeren and the devotion to the Sacred Heart

- Saint Angela of Foligno (d. 1309) and "Lady Poverty"

- Saint John of the Cross: mystic, reformer, poet, and universal psychologist (+1591)

- Blessed Anne of Jesus: a Carmelite nun with mystical gifts (d.1621)

- Catherine Daniélou: a mystical bride of Christ in Brittany

- Saint Margaret Mary sees the "Heart that so loved mankind"

- Jesus makes Maria Droste zu Vischering the messenger of his Divine Heart (d. 1899)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée of Jesus' predictions concerning the Second World War (1922)

- Sister Josefa Menendez, apostle of divine mercy (d. 1923)

- Edith Royer (d. 1924) and the Sacred Heart Basilica of Montmartre

- Rozalia Celak, a mystic with a very special mission (d. 1944)

- Visionaries

- Saint Perpetua delivers her brother from Purgatory (203)

- María de Jesús de Ágreda, abbess and friend of the King of Spain

- Discovery of the Virgin Mary's house in Ephesus (1891)

- Sister Benigna Consolata: the "Little Secretary of Merciful Love" (d. 1916)

- Maria Valtorta's visions match data from the Israel Meteorological Service (1943)

- Berthe Petit's prophecies about the two world wars (d. 1943)

- Maria Valtorta saw only one pyramid at Giza in her visions... and she was right! (1944)

- The location of Saint Peter's village seen in a vision before its archaeological discovery (1945)

- The 700 extraordinary visions of the Gospel received by Maria Valtorta (d. 1961)

- The amazing geological accuracy of Maria Valtorta's writings (d. 1961)

- Maria Valtorta's astronomic observations consistent with her dating system

- Discovery of an ancient princely house in Jerusalem, previously revealed to a mystic (d. 1961)

- Mariette Kerbage, the seer of Aleppo (1982)

- The 20,000 icons of Mariette Kerbage (2002)

- The popes

- The great witnesses of the faith

- Saint Augustine's conversion: "Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?" (386)

- Thomas Cajetan (d. 1534): a life in service of the truth

- Madame Acarie, "the servant of the servants of God" (d. 1618)

- Blaise Pascal (d.1662): Biblical prophecies are evidence

- Madame Élisabeth and the sweet smell of virtue (d. 1794)

- Jacinta, 10, offers her suffering to save souls from hell (d. 1920)

- Father Jean-Édouard Lamy: "another Curé of Ars" (d. 1931)

- Christian civilisation

- The depth of Christian spirituality

- John of the Cross' Path to perfect union with God based on his own experience

- The dogma of the Trinity: an increasingly better understood truth

- The incoherent arguments against Christianity

- The "New Pentecost": modern day, spectacular outpouring of the Holy Spirit

- The Christian faith explains the diversity of religions

- Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle (d.1629) on the mystery of the Incarnation

- Christ's interventions in history

- Marian apparitions and interventions

- The Life-giving Font of Constantinople

- Apparition of Our Lady of La Treille in northern France: prophecy and healings (600)

- Our Lady of Virtues saves the city of Rennes in Bretagne (1357)

- Mary stops the plague epidemic at Mount Berico (1426)

- Our Lady of Miracles heals a paralytic in Saronno (1460)

- Cotignac: the first apparitions of the Modern Era (1519)

- Savona: supernatural origin of the devotion to Our Lady of Mercy (1536)

- The Virgin Mary delivers besieged Christians in Cusco, Peru

- The victory of Lepanto and the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (1571)

- The apparitions to Brother Fiacre (1637)

- The “aldermen's vow”, or the Marian devotion of the people of Lyon (1643)

- Our Lady of Nazareth in Plancoët, Brittany (1644)

- Our Lady of Laghet (1652)

- Saint Joseph’s apparitions in Cotignac, France (1660)

- Heaven confides in a shepherdess of Le Laus (1664-1718)

- Zeitoun, a two-year miracle (1968-1970)

- The Holy Name of Mary and the major victory of Vienna (1683)

- Heaven and earth meet in Colombia: the Las Lajas shrine (1754)

- The five Marian apparitions that traced an "M" over France, and its new pilgrimage route

- A series of Marian apparitions and prophetic messages in Ukraine since the 19th century (1806)

- "Consecrate your parish to the Immaculate Heart of Mary" (1836)

- At La Salette, Mary wept in front of the shepherds (1846)

- Our Lady of Champion, Wisconsin: the first and only approved apparition of Mary in the US (1859)

- Gietrzwald apparitions: heavenly help to a persecuted minority

- The silent apparition of Knock Mhuire in Ireland (1879)

- Mary "Abandoned Mother" appears in a working-class district of Lyon, France (1882)

- The thirty-three apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Beauraing (1932)

- "Our Lady of the Poor" appears eight times in Banneux (1933)

- Fontanelle-Montichiari apparitions of Our Lady "Rosa Mystica" (1947)

- Mary responds to the Vows of the Polish Nation (1956)

- Zeitoun apparitions

- The Virgin Mary comes to France's rescue by appearing at L'Ile Bouchard (1947)

- Maria Esperanza Bianchini and Mary, Mary, Reconciler of Peoples and Nations (1976)

- Luz Amparo and the El Escorial apparitions

- The extraordinary apparitions of Medjugorje and their worldwide impact

- The Virgin Mary prophesied the 1994 Rwandan genocide (1981)

- Our Lady of Soufanieh's apparition and messages to Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Virgin Mary heals a teenager, then appears to him dozens of times (1986)

- Seuca, Romania: apparitions and pleas of the Virgin Mary, "Queen of Light" (1995)

- Angels and their manifestations

- Mont Saint-Michel: Heaven watching over France

- The revelation of the hymn Axion Estin by the Archangel Gabriel (982)

- Angels give a supernatural belt to the chaste Thomas Aquinas (1243)

- The constant presence of demons and angels in the life of St Frances of Rome (d. 1440)

- Mother Yvonne-Aimée escapes from prison with the help of an angel (1943)

- Saved by Angels: The Miracle on Highway 6 (2008)

- Exorcisms in the name of Christ

- A wave of charity unique in the world

- Saint Peter Nolasco: a life dedicated to ransoming enslaved Christians (d. 1245)

- Rita of Cascia forgives her husband's murderer (1404)

- Saint Angela Merici: Christ came to serve, not to be served (d. 1540)

- Saint John of God: a life dedicated to the care of the poor, sick and those with mental disorders (d. 1550)

- Saint Camillus de Lellis, reformer of hospital care (c. 1560)

- Blessed Alix Le Clerc, encouraged by the Virgin Mary to found schools (d. 1622)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), apostle of charity

- Marguerite Bourgeoys, Montreal's first teacher (d. 1700)

- Frédéric Ozanam, inventor of the Church's social doctrine (d. 1853)

- Damian of Molokai: a leper for Christ (d. 1889)

- Pier Giorgio Frassati (d.1925): heroic charity

- Saint Dulce of the Poor, the Good Angel of Bahia (d. 1992)

- Mother Teresa of Calcutta (d. 1997): an unshakeable faith

- Heidi Baker: Bringing God's love to the poor and forgotten of the world

- Amazing miracles

- The miracle of liquefaction of the blood of St. Januarius (d. 431)

- The miracles of Saint Anthony of Padua (d. 1231)

- Saint Pius V and the miracle of the Crucifix (1565)

- Saint Philip Neri calls a teenager back to life (1583)

- The resurrection of Jérôme Genin (1623)

- Saint Francis de Sales brings back to life a victim of drowning (1623)

- Saint John Bosco and the promise kept beyond the grave (1839)

- The day the sun danced at Fatima (1917)

- Pius XII and the miracle of the sun at the Vatican (1950)

- When Blessed Charles de Foucauld saved a young carpenter named Charle (2016)

- Reinhard Bonnke: 89 million conversions (d. 2019)

- Miraculous cures

- The royal touch: the divine thaumaturgic gift granted to French and English monarchs (11th-19th centuries)

- With 7,500 cases of unexplained cures, Lourdes is unique in the world (1858-today)

- Our Lady at Pellevoisin: "I am all merciful" (1876)

- Mariam, the "little thing of Jesus": a saint from East to West (d.1878)

- The miraculous healing of Marie Bailly and the conversion of Dr. Alexis Carrel (1902)

- Gemma Galgani: healed to atone for sinners' faults (d. 1903)

- The miraculous cure of Blessed Maria Giuseppina Catanea

- The extraordinary healing of Alice Benlian in the Church of the Holy Cross in Damascus (1983)

- The approved miracle for the canonization of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1990)

- Healed by St Charbel Makhlouf, her scars bleed each month for the benefit of unbelievers (1993)

- The miracle that led to Brother André's canonisation (1999)

- Bruce Van Natta's intestinal regrowth: an irrefutable miracle (2007)

- He had “zero” chance of living: a baby's miraculous recovery (2015)

- Manouchak, operated on by Saint Charbel (2016)

- How Maya was cured from cancer at Saint Charbel's tomb (2018)

- Preserved bodies of the saints

- Dying in the odour of sanctity

- The body of Saint Cecilia found incorrupt (d. 230)

- Saint Claudius of Besançon: a quiet leader, a calm presence, and a strong belief in the value of prayer (d. 699)

- Stanislaus Kostka's burning love for God (d. 1568)

- Saint Germaine of Pibrac: God's little Cinderella (d. 1601)

- Blessed Antonio Franco, bishop and defender of the poor (d. 1626)

- Giuseppina Faro, servant of God and of the poor (d. 1871)

- The incorrupt body of Marie-Louise Nerbollier, the visionary from Diémoz (d. 1910)

- The great exhumation of Saint Charbel (1950)

- Bilocations

- Inedias

- Levitations

- Lacrimations and miraculous images

- Saint Juan Diego's tilma (1531)

- The Rue du Bac apparitions of the Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré (Paris, 1830)

- Mary weeps in Syracuse (1953)

- Teresa Musco (d.1976): salvation through the Cross

- Soufanieh: A flow of oil from an image of the Virgin Mary, and oozing of oil from the face and hands of Myrna Nazzour (1982)

- The Saidnaya icon exudes a wonderful fragrance (1988)

- Our Lady weeps in a bishop's hands (1995)

- Stigmates

- The venerable Lukarda of Oberweimar shares her spiritual riches with her convent (d. 1309)

- Florida Cevoli: a heart engraved with the cross (d. 1767)

- Blessed Maria Grazia Tarallo, mystic and stigmatist (d. 1912)

- Saint Padre Pio: crucified by Love (1918)

- Elena Aiello: "a Eucharistic soul"

- A Holy Triduum with a Syrian mystic, witnessing the sufferings of Christ (1987)

- A Holy Thursday in Soufanieh (2004)

- Eucharistic miracles

- Lanciano: the first and possibly the greatest Eucharistic miracle (750)

- A host came to her: 11-year-old Imelda received Communion and died in ecstasy (1333)

- Faverney's hosts miraculously saved from fire

- A tsunami recedes before the Blessed Sacrament (1906)

- Buenos Aires miraculous host sent to forensic lab, found to be heart muscle (1996)

- Relics

- The Veil of Veronica, known as the Manoppello Image

- For centuries, the Shroud of Turin was the only negative image in the world

- The Holy Tunic of Argenteuil's fascinating history

- Saint Louis (d. 1270) and the relics of the Passion

- The miraculous rescue of the Shroud of Turin (1997)

- A comparative study of the blood present in Christ's relics

- Jews discover the Messiah

- Francis Xavier Samson Libermann, Jewish convert to Catholicism (1824)

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal and the conversion of Alphonse Ratisbonne (1842)

- Max Jacob: a liberal gay Jewish artist converts to Catholicism (1909)

- Edith Stein - Saint Benedicta of the Cross: "A daughter of Israel who, during the Nazi persecutions, remained united with faith and love to the Crucified Lord, Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, and to her people as a Jew"

- Patrick Elcabache: a Jew discovers the Messiah after his mother is miraculously cured in the name of Jesus

- Olivier's conversion story: from Pesach to the Christian Easter (2000)

- Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (d. 2007): Chosen by God

- Muslim conversions

- He met Jesus while looking for Muhammad (1990)

- Selma's journey to baptism (1996)

- Soumia, converted to Jesus as she hears Christmas carols (2003)

- How Aïsha, a Muslim convert, found Jesus (2004)

- Amir chooses Christ, at the risk of becoming homeless (2004)

- Souad Brahimi: brought to Jesus by Mary (2012)

- Pursued by God: Khadija's story (2023)

- Buddhist conversions

- Atheist conversions

- The conversion of an executioner during the Terror (1830)

- God woos a poet's heart: the story of Paul Claudel's conversion (1886)

- From agnostic to Catholic Trappist monk (1909)

- Dazzled by God: Madeleine Delbrêl's story (1924)

- C.S. Lewis, the reluctant convert (1931)

- The day André Frossard met Christ in Paris (1935)

- MC Solaar's rapper converts after experiencing Jesus' pains on the cross

- Father Sébastien Brière, converted at Medjugorje (2003)

- Franca Sozzani, the "Pope of fashion" who wanted to meet the Pope (2016)

- Nelly Gillant: from Reiki Master to Disciple of Christ (2018)

- Testimonies of encounters with Christ

- Near-death experiences (NDEs) confirm Catholic doctrine on the Four Last Things

- The NDE of Saint Christina the Astonishing, a source of conversion to Christ (1170)

- Jesus audibly calls Alphonsus Liguori to follow him (1723)

- Blessed Dina Bélanger (d. 1929): loving God and letting Jesus and Mary do their job

- Gabrielle Bossis: He and I

- André Levet's conversion in prison

- Journey between heaven and hell: a "near-death experience" (1971)

- Jesus' message to Myrna Nazzour (1984)

- Alicja Lenczewska: conversations with Jesus (1985)

- Vassula Ryden and the "True Life in God" (1985)

- Nahed Mahmoud Metwalli: from persecutor to persecuted (1987)

- The Bible verse that converted a young Algerian named Elie (2000)

- Invited to the celestial court: the story of Chantal (2017)

- Providential stories

- The superhuman intuition of Saint Pachomius the Great

- Ambrose of Milan finds the bodies of the martyrs Gervasius and Protasius (386)

- Germanus of Auxerre's prophecy about Saint Genevieve's future mission, and protection of the young woman (446)

- Seven golden stars reveal the future location of the Grande Chartreuse Monastery (1132)

- The supernatural reconciliation of the Duke of Aquitaine (1134)

- Saint Zita and the miracle of the cloak (13th c.)

- Joan of Arc: "the most beautiful story in the world"

- John of Capistrano saves the Church and Europe (1456)

- A celestial music comforts Elisabetta Picenardi on her deathbed (d. 1468)

- Gury of Kazan: freed from his prison by a "great light" (1520)

- The strange adventure of Yves Nicolazic (1623)

- Julien Maunoir miraculously learns Breton (1626)

- Pierre de Keriolet: with Mary, one cannot be lost (1636)

- How Korea evangelized itself (18th century)

- A hundred years before it happened, Saint Andrew Bobola predicted that Poland would be back on the map (1819)

- The prophetic poem about John Paul II (1840)

- Don Bosco's angel dog: Grigio (1854)

- The purifying flames of Sophie-Thérèse de Soubiran La Louvière (1861)

- Thérèse of Lisieux saved countless soldiers during the Great War

- Lost for over a century, a Russian icon reappears (1930)

- In 1947, a rosary crusade liberated Austria from the Soviets (1946-1955)

- The discovery of the tomb of Saint Peter in Rome (1949)

- He should have died of hypothermia in Soviet jails (1972)

- God protects a secret agent (1975)

- Flowing lava stops at church doors (1977)

- A protective hand saved John Paul II and led to happy consequences (1981)

- Mary Undoer of Knots: Pope Francis' gift to the world (1986)

- Edmond Fricoteaux's providential discovery of the statue of Our Lady of France (1988)

- The Virgin Mary frees a Vietnamese bishop from prison (1988)

- The miracles of Saint Juliana of Nicomedia (1994)

- Global launch of "Pilgrim Virgins" was made possible by God's Providence (1996)

- The providential finding of the Mary of Nazareth International Center's future site (2000)

- Syrian Monastery shielded from danger multiple times (2011-2020)

Les saints

n°322

France

1757 - 1849

Camille de Soyécourt, filled with divine fortitude

Having survived the persecutions of the Reign of Terror, which had wiped out her family and destroyed her religious order, deprived of her family's immense fortune, isolated, burdened with worries, guardian of an orphan nephew, Sister Thérèse-Camille de l'Enfant-Jésus, born Camille de Soyécourt, in 1795, could have been lamenting her fate. But instead, with unfailing courage and determination, this 37-year-old woman faced up to all the difficulties and, after fighting to recover her inheritance, spent it on a work deemed impossible in the aftermath of the French Revolution: to restore the Carmelite Order in France, with God's help and despite political pressure.

Shutterstock, Rawpixel.com

Les raisons d'y croire :

- At the age of fifteen, Camille found the courage to tell her parents that she aspired to a cloistered and contemplative life, but the Soyécourt family, who wanted to arrange a good marriage for her, opposed her plan. The young girl, so gentle, devoted and respectful, retorted that in that case, she would wait until she came of age. Since, under the Ancien Régime, the age of majority was set at twenty-five, Camille knew she would face a long struggle with her family for a decade. It took great determination and total trust in providence to dare to do this, with the intention of remaining faithful to her promise; without divine help, she would never have succeeded.

- The Soyécourts were skilful in not coercing their daughter or making her life impossible. On the contrary, they gave her a taste of the pleasures and advantages that her rank and fortune could bring her. Leisure activities, parties, splendid dresses and the promise of a happy, easy and carefree life were all presented to her. But just as she was about to give in to them, she immersed herself in the practice of prayer and became more firmly rooted than ever in the vocation she could easily have abandoned.

- In February 1784, Camille, now of age, entered the Carmelite nuns with the support of Princess Louise of France, the daughter of Louis XV, who was cloistered in the Carmelite convent of Saint-Denis, setting an example of complete self-renunciation. She made her solemn profession there the following year and took the religious name of Sister Thérèse-Camille of the Child Jesus. Accustomed to an easy and comfortable life, adaptating to convent life was difficult for her, but she endured everything in order to remain faithful to God's plan for her. After she succeeded, one might have expected that the hardest part was gone and her trials were over. In fact, the worst was yet to come.

- When the French Revolution began and made the disappearance of Roman Catholicism one of its priorities, the Soyécourts, certain that their daughter's Carmelite convent was going to close and that the sisters were going to be expelled, asked Camille to join them on their estate in Picardy, where they thought she would be safe with them. But Camille refused, faithful to her religious vows, fully aware of the danger. However, it was early autumn 1792 and, in Paris and the provinces, there had just been appalling massacres of so-called suspects, in other words real or supposed opponents of the Revolution, many of them priests - the killers targeting Catholics and the clergy in particular. We now know that martyrdom was a real possibility. In these conditions, it took exceptional courage not to seek shelter and hide instead.

- After the closure of her Carmelite convent, she and a few of her sisters moved to rue Mouffetard, on the edge of the Latin Quarter, where they not only prayed, but also helped to maintain clandestine worship and to hide rebellious priests - both activities punishable by death. The Carmelites were arrested on Good Friday (29 March 1793) and released in June. Camille, despite the three months in prison, did not give in. She was still determined to not join her parents in Picardy.

- Forgetting the wrongs her family might have done her by thwarting her vocation, Camille then devoted herself to alleviating the misfortunes of her parents and sister, who had been arrested and were in prison, giving them all the material and moral help she could. The courage and self-sacrifice shown by Sister Thérèse-Camille of the Child Jesus are, once again, exceptional and reflect a heroic practice of the virtue of strength, granted by God.

- Camille would have been justified in thinking that life events had freed her from her vows and that she could without fail return to the secular life, as many others did. However, she was certain that her personal role was beginning and that God had a mission for her. In 1795, when the religious persecution was not yet over, she rented accommodation and set about finding her former companions, and then all the Carmelite nuns who, like her, wanted to return to convent life. A clandestine Carmelite convent was reborn on rue Saint-Jacques. Once again, Camille de Soyécourt showed determination and courage given to her from above.

- Having succeeded in recovering almost the entirety of her family's enormous fortune, thanks to special permission from the Pope which dispensed her from her vow of poverty, Camille might have been tempted to keep it for herself. But dismayed by the extent of the ruins left by the Revolution and the colossal task of rebuilding that lay ahead for the Church, the woman known as "the millionaire Carmelite" devoted her entire fortune to the objectives she had set herself: the restoration of Carmel and Catholicism in France.

- Camille bought the Carmelite convent in Paris and re-established a clandestine Carmelite convent, where she brought together surviving Carmelite nuns who had been separated from their companions and wanted to return to the contemplative life. This was only the beginning: determined to use her money for the good of the Church, Mother Thérèse-Camille of the Child Jesus helped to save many other carmelite convents, churches and religious institutes that had been damaged during the Revolution, both in Paris and in the provinces. In this case, as in all the others, the foundress of Carmel in France was clearly acting under God's direction.

- Camille de Soyécourt died in 1849, on 9 May, aged ninety-one. Carmel and the Church in France owe her a great deal.

Synthèse :

The birth in Paris, on 25 June 1757, of Camille Marie Françoise de Soyécourt was not an occasion for joy for her noble and very wealthy family. They had hoped for a boy, but instead it was a third daughter... The disappointment was such that when asked: "What name should we give her?" one of her aunts replied: "Miss one too many!"To correct this mean-spirited remark, someone exclaimed: "Who knows if this little one won't be the honour and consolation of her family?"This last remark was prophetic, for the child would indeed be the glory of her lineage and would play a providential role in the restoration of Catholicism in France.

Camille was fifteen when her parents decided to make a good match for her, that is, for the family. It was a normal age for the time and for her social class. They set their sights on a well-titled and wealthy suitor, who had only one major flaw for such a young girl: he was nearly sixty... However, it was not this age difference that upset Mademoiselle de Soyécourt, but rather the prospect that this unfortunate marriage plan would prevent her from fulfilling her secret aspiration: to enter a Carmelite convent. As an adult, she would later be capable of standing up to Napoleon or imposing her views on the Pope and the Cardinals, but she was still just an adolescent, petrified of her parents, and she didn't dare express her repugnance to them. Naive and ignorant of the realities of married life, she was about to consent to this union, in the hope that such a great old man would soon leave her a widow and that, emancipated, she would be able to enter the convent. But God wanted her all to himself and, before the date set for the wedding, the fiancé died unexpectedly. Camille was saved. From then on, nothing would stop her from defending her vocation.

After overcoming her taste for worldly pleasures and her parents' reluctance, Camille de Soyécourt entered the Carmelite convent in 1784 and survived the Reign of Terror, during which she lost her entire family. Her parents were arrested at the end of November 1793 (along with one of their eldest daughters) and imprisoned - her father in the former male Carmelite convent, now a prison and already the scene of the massacre of one hundred and two priests and seminarians on 2 and 3 September 1792, and her mother in the former Sainte-Pélagie convent, where she died of illness. Monsieur de Soyécourt and Camille's sister were guillotined at the end of July 1794, shortly before the fall of Robespierre.

Orphaned from her family and separated from her spiritual family - scattered, hidden and seemingly definitively destroyed - the young woman was alone, without material support or a penny to her name, since the enormous family fortune had been confiscated by the Republic; she had also had to take in the son of her executed sister, whom she had to bring up and feed. Anyone else would have given up, but not Camille. She was working to salvage what could be salvaged and, to ensure her nephew's future and her own, to recover everything that could be salvaged from the family estate. Camille was also taking steps to recover the family fortune, of which she remained the sole heiress. But one scruple stopped her: she had taken a vow of poverty. The priests she hid, helped and rescued advised her to go to Pope Pius VI and tell him that the money would be used to meet the needs of the Church in France. The Pope exceptionally dispensed her from her vow of poverty. Mademoiselle de Soyécourt thus recovered several millions: she was now very rich.

Camille bought back the former convent of the Discalced Carmelites, which had been threatened with demolition - in memory of her father, who lived there for his last months, and the martyred priests who were massacred there - and recreated a clandestine Carmelite convent, in which she brought together the surviving Carmelite nuns, separated from their companions and wishing to return to the contemplative life. She reopened the Carmelite convent without authorisation,because the contemplative life, deemed unnecessary, was not part of Bonaparte's plans for the restoration of Catholicism. Determined to use her money for the good of the Church, Mother Thérèse-Camille of the Child Jesus helped to save many other convents that she bought, both in Paris and in the provinces. She not only restored sixty houses of Carmel, but also provided the funds needed to revive dozens of religious institutes destroyed during the Revolution.

It was this work that she did not hesitate to jeopardise when, in 1810, she joined the Catholic resistance to Napoleon, who had invaded the Papal States and annexed them to the Empire before imprisoning Pope Pius VII. Even though these actions were symbolic - such as the distribution of leaflets hostile to the emperor's religious policy, which did not represent any real danger to him - Napoleon, exasperated at seeing Catholics letting him down, ordered the police to be severe. He demoted certain cardinals exiled in the provinces, who were then forced to return to the state of ordinary priests, earning them the nickname of "black cardinals", because they had condemned his remarriage to Marie-Louise of Austria. Although under house arrest, some of them travelled to the capital as they pleased, thanks to the help of a certain "Lady Camilla". The police identified her as the Reverend Mother Thérèse-Camille of the Child Jesus,the "millionaire Carmelite nun", who was not afraid of anything or anyone. They decided to arrest her in the hope of taking down her network.

This was done in 1811, but Mother Thérèse-Camille of the Child Jesus kept silent and did not give up her "accomplices", even though she knew that the Emperor was furious and could close her convents, destroying her work. Confident, she put her trust in providence and was rewarded for it. A high prelate vouched for her, swearing that she had no subversive agenda against the government. She was exiled to Guise, but continued to run her networks and even managed to return to her Parisian Carmelite convent. To avoid ridicule, the government pardoned her on health grounds. Admiring her, Napoleon deplored not having in his entourage someone as loyal and devoted to him as the nun was to the Pope. In retaliation, he had the religious institutes that opposed his views closed, but in 1813 he officially acknowledged the return of the Carmelite order in France.

Anne Bernet is a Church History specialist, postulator of a cause for beatification, and journalist for a number of Catholic media. She is the author of over forty books, most of them on the topic of sanctity.

Aller plus loin :

Vie de la révérende mère Thérèse-Camille de Soyécourt by Mère Éléonore du Saint-Sacrement (published anonymously, the work is sometimes also attributed to Mother Saint-Jérôme), , 1878. Available on demand from Eyrolles and can be consulted online.

En savoir plus :- Cardinal Baudrillard, La très vénérable Camille de Soyécourt ou celle qui n'a eu pas peur, Albin Michel, 1941.

- C. Tavernier, "Mère Camille de Soyécourt et les cardinaux noirs", Revue d'histoire de l'Église de France, vol. 42, 1956.

- The Aleteia article: " Camille de Soyecourt, l'intrépide carmélite de la Révolution ".

LES RAISONS DE LA SEMAINE

L’Église ,

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Saint Simon Stock reçoit le scapulaire du Mont Carmel des mains de la Vierge Marie

Les saints

Saint Pascal Baylon, humble berger

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Stigmates

Sainte Rita de Cascia, celle qui espère contre toute espérance

Les saints

L’étrange barque de saint Basile de Riazan

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Antoine de Padoue, le « saint que tout le monde aime »

Les saints ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

L’extraordinaire conversion de Micheline de Pesaro

Les saints ,

Les anges et leurs manifestations ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Antoine-Marie Zaccaria, médecin des corps et des âmes

Les saints

Les saints époux Louis et Zélie Martin

Les saints ,

La profondeur de la spiritualité chrétienne

Frère Marcel Van, une « étoile s’est levée en Orient »

Les saints

Sainte Anne et saint Joachim, parents de la Vierge Marie

Les saints

Saint Loup, l’évêque qui fit rebrousser chemin à Attila

Les saints

Saint Ignace de Loyola : à la plus grande gloire de Dieu

Les saints

Saint Nazaire, apôtre et martyre

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Saint Jean-Marie Vianney, la gloire mondiale d’un petit curé de campagne

Les moines ,

Les saints

Saint Dominique de Guzman, athlète de la foi

Les saints ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Sainte Faustine, apôtre de la divine miséricorde

Les moines ,

Lévitations ,

Stigmates ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Saint François, le pauvre d’Assise

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Ignace d’Antioche : successeur des apôtres et témoin de l’Évangile

Les saints

Antoine-Marie Claret, un tisserand devenu ambassadeur du Christ

Les saints

Alphonse Rodriguez, le saint portier jésuite

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Bilocations

Martin de Porrès revient hâter sa béatification

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants

Saint Martin de Tours, père de la France chrétienne

Les saints

Saint Grégoire le Thaumaturge

Les saints ,

Une vague de charité unique au monde ,

Corps conservés des saints

Virginia Centurione Bracelli : quand toutes les difficultés s’aplanissent

Les saints

Lorsque le moine Seraphim contemple le Saint-Esprit

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Pierre Thomas : une confiance en la Vierge Marie à toute épreuve

Les saints

À Grenoble, le « saint abbé Gerin »

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Gabriel de l’Addolorata, le « jardinier de la Sainte Vierge »

Les saints ,

Les mystiques ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Sainte Rose de Viterbe : comment la prière change le monde

Les saints

Bienheureux Francisco Palau y Quer, un amoureux de l’Église

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

La maturité surnaturelle de Francisco Marto, « consolateur de Dieu »

L’Église ,

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

San Simón Stock recibe el escapulario del Carmen de manos de la Virgen María

Les saints

San Pascual Baylon, humilde pastor

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Stigmates

Santa Rita de Casia, la que espera contra toda esperanza

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Bernadette Soubirous, bergère qui vit la Vierge

Les saints ,

Histoires providentielles

L’absolue confiance en Dieu de sainte Agnès de Montepulciano

Les saints

Sainte Catherine de Gênes, ou le feu de l’amour de Dieu

Les saints

Sainte Marie de l’Incarnation, « la sainte Thérèse du Nouveau Monde »

Les saints

Rosa Venerini ou la parfaite volonté de Dieu

L’Église ,

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Saint Simon Stock reçoit le scapulaire du Mont Carmel des mains de la Vierge Marie

Les saints

Saint Paschal Baylón: from humble shepherd to the glory of sainthood

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Stigmates

Saint Rita of Cascia: hoping against all hope

Les saints

Camille de Soyécourt, comblée par Dieu de la vertu de force

L’Église ,

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

San Simone Stock ricevette dalle mani della Vergine Maria lo scapolare del Monte Carmelo

Les saints

San Pascal Baylon, umile pastore

Les saints

François de Girolamo lit dans les cœurs

Les saints ,

La profondeur de la spiritualité chrétienne

Hermano Marcel Van, "una estrella ha nacido en Oriente".

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Stigmates

Santa Rita da Cascia, colei che spera contro ogni speranza

Les saints

La extraña barca de San Basilio de Riazán

Les saints

Jeanne-Antide Thouret : partout où Dieu voudra l’appeler

Les saints

The unusual boat of Saint Basil of Ryazan

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Anthony of Padua: "everyone’s saint"

Les saints ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

The extraordinary conversion of Michelina of Pesaro

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

San Antonio de Padua, el "santo que todo el mundo ama".

Les saints ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

La extraordinaria conversión de Micheline de Pesaro

Les saints

Saint Augustin de Cantorbéry apporte la bonne nouvelle sur la terre des Angles

Les saints ,

Les anges et leurs manifestations ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Anthony Mary Zaccaria, physician of bodies and souls

Les saints ,

La profondeur de la spiritualité chrétienne

Brother Marcel Van: a "star has risen in the East"

Les saints

Saints Louis and Zelie Martin

Les saints

La strana barca di San Basilio di Ryazan

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

Sant'Antonio da Padova, il "santo che tutti amano"

Les saints ,

Les anges et leurs manifestations ,

Corps conservés des saints

San Antonio María Zaccaria, médico de cuerpos y almas

Les saints

Los Santos esposos Luis y Celia Martin

Les saints

Saint Rainer de Pise : la conversion miraculeuse d’un riche négociant

Les saints ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

La straordinaria conversione di Michelina da Pesaro

Les saints

Saint Jean-Baptiste, témoin du Christ annoncé par les prophètes

Les saints ,

Les anges et leurs manifestations ,

Corps conservés des saints

Sant'Antonio Maria Zaccaria, medico del corpo e dell'anima

Les saints

Saint Bernardin Realino répond à l’appel divin

Les saints

Santa Ana y San Joaquín, padres de la Virgen María

Les saints

San Nazario, apóstol y mártir

Les saints

San Lupo, el obispo que hizo retroceder a Atila

Les saints ,

Corps conservés des saints

Sainte Élisabeth du Portugal, une rose en royauté

Les saints

San Ignacio de Loyola: a la mayor gloria de Dios

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

San Juan María Vianney, la gloria mundial de un cura de pueblo

Les moines ,

Les saints

Santo Domingo de Guzmán, atleta de la fe

Les saints ,

La profondeur de la spiritualité chrétienne

Fratel Marcel Van, "una stella è sorta in Oriente"

Les saints

I santi sposi Louis e Zélie Martin

Les saints

Saints Anne and Joachim, parents of the Virgin Mary

Les saints

La confiance en Dieu de sainte Marie-Madeleine Postel

Les saints

Saint Nazarius, apostle and martyr

Les saints

Saint Lupus, the bishop who saved his city from the Huns

Les saints

Saint Ignatius of Loyola: "For the greater glory of God"

Les saints

Sant'Anna e San Gioacchino, genitori della Vergine Maria

Les saints

San Nazario, apostolo e martire

Les saints

San Lupo, il vescovo che fece indietreggiare Attila

Les saints

Sant'Ignazio di Loyola: per la maggior gloria di Dio

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Saint John Vianney (d. 1859): the global fame of a humble village priest

Les moines ,

Les saints

Saint Dominic de Guzman: an athlete of the faith

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

San Giovanni Maria Vianney, la gloria mondiale di un piccolo curato di campagna

Les moines ,

Les saints

San Domenico di Guzmán, atleta della fede

Les saints ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Santa Faustina, apóstol de la Divina Misericordia

Les saints

Jean Eudes, époux du Cœur Immaculé de Marie

Les saints ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Saint Faustina, apostle of the Divine Mercy

Les saints

Syméon monte sur une colonne pour demeurer seul avec le Christ

Les saints ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Santa Faustina, apostola della divina misericordia

Les moines ,

Lévitations ,

Stigmates ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

Saint Francis, the poor man of Assisi

Les moines ,

Lévitations ,

Stigmates ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

San Francisco, el pobre de Asís

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Ignacio de Antioquía: sucesor de los apóstoles y testigo del Evangelio

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Ignatius of Antioch: successor of the apostles and witness to the Gospel

Les moines ,

Lévitations ,

Stigmates ,

Conversions d'athées ,

Témoignages de rencontres avec le Christ

San Francesco, il poverello d'Assisi

Les saints

Thérèse Couderc remet tout entre les mains de Marie

Les saints

Brother Alphonsus Rodríguez, SJ: the "holy doorkeeper"

Les saints

Alonso Rodríguez, el santo jesuita portero

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Bilocations

Martin de Porrès regresa para acelerar su beatificación

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Bilocations

Martin de Porres returns to speed up his beatification

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Newman cherche la véritable Église du Christ

Les saints ,

Les grands témoins de la foi

Ignazio di Antiochia: successore degli apostoli e testimone del Vangelo

Les saints

Dieu parle par la bouche de la bienheureuse Madeleine de Panattieri

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants

Saint Martin of Tours: patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism

Les saints

La « légende » des saints n’est pas un mythe

Les saints

Pierre d’Alcantara, à qui Dieu ne refuse rien

Les saints

Saint Gregory the Miracle-Worker

Les saints

Alfonso Rodríguez, il santo portinaio gesuita

Les saints

Hilaire de Mende, un saint évêque thaumaturge

Les saints

Celina Chludzinska, une vie entre les mains de Dieu

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants

San Martín de Tours, padre de la Francia cristiana

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Bilocations

Martín de Porres torna per accelerare la sua beatificazione

Les saints

San Gregorio Taumaturgo

Les saints

Le succès étonnant des prédications de saint Ange d’Acri

Les saints ,

Des miracles étonnants

San Martino di Tours, padre della Francia cristiana

Les saints

San Gregorio Taumaturgo

Les saints ,

Une vague de charité unique au monde ,

Corps conservés des saints

Virginia Centurione Bracelli: When God is the only goal, all difficulties are overcome

Les saints ,

Une vague de charité unique au monde ,

Corps conservés des saints

Virginia Centurione Bracelli: cuando las cosas se ponen difíciles

Les saints

Le mariage virginal de bienheureuse Delphine de Sabran

Les saints

Jacques de la Marche transmet la foi catholique à travers l’Europe

Les saints ,

Une vague de charité unique au monde ,

Corps conservés des saints

Virginia Centurione Bracelli: quando tutte le difficoltà vengono meno

Les saints

Seraphim of Sarov: the purpose of the Christian life is to acquire the Holy Spirit

Les saints ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Née aveugle, sainte Odile retrouve la vue lors de son baptême

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints

Saint Peter Thomas: a steadfast trust in the Virgin Mary

Les saints

Cuando el monje Serafín contempla al Espíritu Santo

Les saints

Gatien, apôtre de la Touraine

Les saints

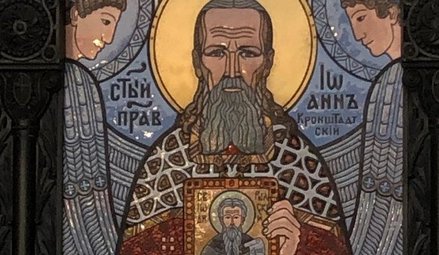

La vie en Jésus Christ de Jean de Cronstadt

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints

San Pedro Tomás: una confianza inquebrantable en la Virgen María

Les saints

Quando il monaco Serafino contemplava lo Spirito Santo

Les saints

La grande conversion de Fabiola

Les saints

Gaspard del Bufalo, le prêtre qui a dit non à Napoléon

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints

San Pietro Tommaso e la sua fiducia incrollabile nella Vergine Maria

Les saints

Mélanie la Jeune : par le chas d’une aiguille

Les saints

Sainte Geneviève, patronne de Paris

Les moines ,

Les saints

Saint André Bessette, serviteur de saint Joseph

Les saints

Saint Remi, l’évêque qui baptisa le roi des Francs

Les saints

Father Gerin, the holy priest of Grenoble

Les saints

Saint Ildefonse de Tolède, défenseur de la Vierge Marie

Les saints

A Grenoble, il "santo abate Gerin"

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, the "Gardener of the Blessed Virgin"

Les saints

Saint Avit de Vienne affirme la divinité de Jésus

Les saints

Sainte Joséphine Bakhita, de la souffrance à l’amour

Les saints

En Grenoble, el "santo abate Gerin".

Les saints ,

Les mystiques ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Saint Rose of Viterbo: how prayer changes the world

Les saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Claude La Colombière prédit son emprisonnement

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Gabriel de l'Addolorata, el "jardinero de la Virgen María"

Les saints ,

Les mystiques ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Santa Rosa de Viterbo: cómo la oración cambia el mundo

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales ,

Guérisons miraculeuses

Gabriele dell'Addolorata, il "giardiniere della Vergine Maria"

Les saints

Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer: a lover of the Church

Les saints

Beato Francisco Palau y Quer, amante de la Iglesia

Les saints ,

Les mystiques ,

Des miracles étonnants ,

Corps conservés des saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Santa Rosa da Viterbo: come la preghiera cambia il mondo

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

La madurez sobrenatural de Francisco Marto, "consolador de Dios".

Les saints

Le pacte de la comtesse Molé avec la Croix de Jésus-Christ

Les saints

Il beato Francisco Palau y Quer, amante della Chiesa

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

The supernatural maturity of Francisco Marto, “contemplative consoler of God”

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Bernadette Soubirous, the shepherdess who saw the Virgin Mary

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales

Bernadette Soubirous, la pastora que vio a la Virgen María

Les saints ,

Histoires providentielles

Saint Agnes of Montepulciano's complete God-confidence

Les saints ,

Les apparitions et interventions mariales